Journey stories

This semester I’m teaching a course on the literature of journey and quest with my colleague William Graham. The stories we read teach us, week after week, that there are things we cannot know about the possibilities our humanity holds until we detach ourselves from what is familiar and move into unknown territory. We follow in the footsteps of travelers who come back from their journeys with new information about what it means to be alive.

When we read the Epic of Gilgamesh, in which the hero travels to the ends of the earth searching for a solution to his mortality, Bill always tells our students a story about the teacher with whom he studied that tale. Bill describes his teacher reading aloud ancient hymns to the Mesopotamian gods—the corn gods and the rain gods, the gods of the mountains, and the gods of the marsh—with tears running down his face. These gods were profoundly linked to human needs that are the same now as they were millennia ago: the human need for a climate that sustains life, and for food and nourishment. With his tears, Bill’s teacher acknowledged and honored the human needs that we share with everyone who’s ever lived.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

I’ve seen tears on Bill’s face in the classroom as well. When he leads us through the journey of Moses and the people of Israel in the book of Exodus, he reads from the speech in which Martin Luther King Jr. compares himself to Moses on Mount Nebo, seeing the Promised Land but not knowing if he’ll cross into it himself. Bill wants to show us how the Exodus journey has imprinted itself on other journeys, how its pattern continues to shape our own stories. His tears bear witness to the good news that these journey stories carry within them: that things do not have to be as they are; that new forms of community can come into being; that the world can change.

In his Confessions, St. Augustine berated his boyhood self for weeping over the death of Dido when he read the Aeneid but remaining dry-eyed over the story of Christ’s passion. As many readers have noted, Augustine was awfully hard on his young self. Even C. S. Lewis, reflecting on his own childhood, acknowledged that it was “so hard to feel as one was told one ought to feel about God or the sufferings of Christ.” Augustine thought he had wept over the wrong story. But perhaps he tried too hard to keep those stories separate. The human desire to transcend the circumstances of our lives and the human experience of being made vulnerable by love that are reflected in Virgil’s story are by no means alien to the Christian one.

If you’re looking for a new way to enter the Lenten journey this year, add a journey story to your Lenten reading. Follow Gilgamesh to the ends of the earth or the Knights of the Round Table into trackless parts of the forest. Follow Teresa of Ávila into the interior castle or Shusaku Endo’s pilgrims to the banks of the Ganges. Follow the Buddha as he leaves the comfort of his father’s palace or Haiku poet Bashō as he travels to the deep north of Japan. Follow Virginia Woolf’s characters to the lighthouse or Cormac McCarthy’s father and son in The Road, as they move across the ashy landscape of postapocalyptic America.

The story of Jesus is a unique story. It is the gospel, the good news. But like the incarnation itself, it draws its power not only from its uniqueness but also from being a story among other stories. By the time it reaches us, the story of Jesus’ 40 days in the desert and the story of his journey toward Jerusalem are resonant with echoes from earlier narratives: Elijah’s journey to Mount Horeb, the journey of the people of Israel through the wilderness, the journey of Abraham and Isaac up Mount Moriah, the journey of humanity out of paradise and into the contingent world. In turn, the story of Jesus patterns many of the stories that come later and shines its light on them.

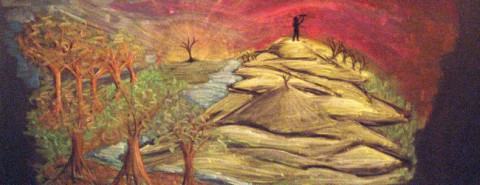

During Lent we seek to have Jesus’ story provide the pattern for our lives. The Lenten journey invites us to detach ourselves from the habits and comforts that protect and sustain our status quo and to step out into a disorienting space. This is where Gilgamesh goes about mourning in the skin of a lion. It’s the obscure wood in which Dante wakes up. It’s the desert in which the people of Israel wander. The anthropologists call this liminal space, where our perspective can shift, where we become vulnerable to transformation, and where new forms of being and living may be discovered.

Jesus invites us into this liminal space, a space he explored to its very limits. Placing his story next to the stories of others whose humanity he shared illuminates the radical possibilities of our shared human journey.