Feeling forgiven helps us forgive others, study says

“Forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us.” Many religious people count on God’s forgiveness, but find it difficult to put aside feelings of bitterness and resentment to pardon others.

A new study, however, shows the two spiritual goals are related. Individuals who believe that a loving God forgives them are far more likely to turn around and absolve others, according to several research projects.

Trust in God’s forgiveness, studies find, also may make it more likely for individuals to forgive themselves, which in turn seems to make it easier for them to extend mercy to others.

Accepting God’s forgiveness and pardoning others is also associated with substantial health benefits. Feeling of anger, fear, shame and guilt over the sins of others and personal transgressions tend to dissipate.

Among the takeaways for religious leaders and people in the pews are that an active faith appears to promote forgiveness. And how human beings perceive God—as a loving father who forgives them unconditionally or as a distant sovereign who judges them—makes a difference in the way they treat friends, coworkers, relatives and neighbors.

“The kind of God we teach about matters,” says researcher Daniel Escher of the University of Notre Dame.

Forgiveness is a deeply personal issue, and no one standard can be applied to individual situations. Many people find forgiving others lifts heavy burdens of anger and resentment from their hearts. But some, such as victims of domestic violence or sexual abuse, find that forgiveness can be offered too quickly or too easily and so is hollow. It could also be potentially harmful if it prevents people from acknowledging their own suffering and makes them less able to distance and protect themselves from transgressors.

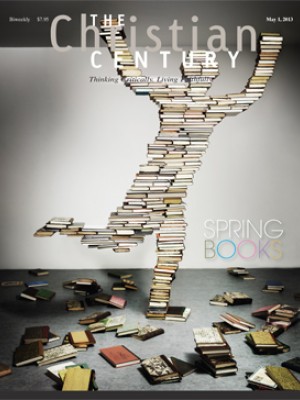

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

In general, however, forgiveness is linked to better mental and physical health. Research has shown people who scored high on forgiveness scales had significantly lower levels of blood pressure, anxiety and depression, and relatively high self-esteem and life satisfaction.

Escher’s study, using data from the 1998 General Social Survey, pointed to long-term effects of religious practice, with those affiliated with a religious tradition since age 16 showing a greater likelihood to be forgiving.

“What seems to matter in promoting forgiveness . . . is that a person adheres to a religion or a denomination; on the whole, the religiously unaffiliated have less of a propensity to forgive,” Escher wrote in the March issue of the Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion.

The findings also indicated that the setting of conditions on forgiveness, such as requiring acts of contrition, is associated with greater psychological distress. Researchers Neal Krause of the University of Michigan and Christopher Ellison of the University of Texas at San Antonio reported their findings a decade ago in the Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion.

“Those that forgive unconditionally are the ones that seem to have better mental health,” Krause said in an interview. “You get the hurt behind you.”

How people are treated at church— whether their fellow worshipers model compassion or judgment—also seems to make a difference. In a separate study of older adults published in the Review of Religious Research, Krause found results suggesting participants who were more satisfied with the emotional support they received from church members were more likely to forgive themselves than those who were not satisfied with the support they received.

Overall, the research seems to support the effectiveness of efforts to promote forgiveness. Churchgoers at a typical service are likely to hear prayers and sermons and experience rituals urging people to confess their sins and offer forgiveness to others.

But some sociologists also note what worshipers are less likely to hear is encouragement to accept divine forgiveness for their own transgressions. Notre Dame’s Escher says that religious leaders may want to consider ways to incorporate rituals encouraging individuals to accept forgiveness of their own sins into more aspects of services. Perhaps even a prayer that goes something like: “Forgive your neighbor as yourself.” — thearda.com

Reprinted with permission from the Association of Religion Data Archives.