Church of William Harris

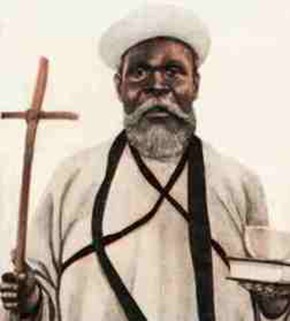

This year marks the centennial of an explosive episode in modern Christian history. In July 1913, a prophetic evangelist named William Wadé Harris began his march across the French colony of Ivory Coast, calling people to live purely and to reject pagan religion. The astonishing impact he achieved suggests the deep popular thirst for his words and for the distinctly African style in which he clothed it. Some observers claimed he won 100,000 converts within a few months—until panicked French authorities drove him out of the country. Although prophets abounded in 20th-century Africa, Harris’s sweeping religious revolution marked the beginning of a critical new phase of mass evangelization.

Harris’s name is familiar enough in the story of Christian Africa, and Mark Noll and others have listed him among the century’s most significant Christian figures. His life repays study for what it tells us about his mission’s appeal. It also reminds us of a horrendous, and largely forgotten, aspect of the Western Christian encounter with Africa.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Born in 1860, Harris came from the Grebo people of Liberia—a context critical to understanding him. Anyone interested in antebellum American history knows the debate over whether freed slaves should be resettled in Africa and how that idea led to the creation of the colony of Liberia in 1822. Few nonspecialists, though, know how grimly that scheme worked out.

The American sponsors made no effort to determine the views of the existing residents about that settlement. They worked on the theory that, well, they’re all Africans, so surely they’ll all get along. The Americanized black elite—the Americo-Liberians—seemed to represent progress and modernity. The capital, Monrovia, took its name from a U.S. president, and the Liberian flag was a variant of the stars and stripes. Until 1980, the ruling party was the True Whigs. Who could criticize such a Little America?

Unfortunately, that elite also inherited American ideas of racial hierarchy. It positioned itself as the master caste and native Africans as the underclass. Although the elite made up only about 5 percent of the population, it denied political rights to the indigenous Kru people, whose various groups included the Grebo. These divisions shaped the politics of the new nation, and open warfare erupted repeatedly over the next century. While the Americo-Liberians presented a civilized face to the West, they maintained their power by massacre and torture.

Christianity made very slow progress among native peoples, for the creed was associated with an exploitative master race, even if, in this instance, the bosses were themselves of African descent. In Liberia, as in South Africa or the Congo, it took a rare genius to distinguish between the authentic core of Christianity and its imperialist trappings.

William Wadé Harris was such a person. He became a Christian about 1881, dividing his loyalty between the Episcopal and Methodist churches. Accepting Christianity, though, did not mean abandoning his people’s struggle for justice, and in 1909 he was imprisoned for trying to replace the Liberian regime with direct British rule. It was while in prison that he received his prophetic calling, reportedly from the Archangel Gabriel. On his release, he began his march into the Ivory Coast and Ghana, initially among fellow Grebo but soon reaching across tribal lines.

Harris proclaimed a Christ who was not the property of the master race, whether French, British or Americo-Liberian. He appeared in African style, wearing a white robe and a turban, carrying a bamboo cross and a baptism bowl and accompanied by his wives.

Critically, his mission recognized the deadly serious nature of the native faiths with their belief in ancestors and witchcraft, which Western missionaries mocked. When Harris reached a village, his followers’ first step was to collect and burn the pagan fetishes. The scene could have been taken from a churchly account of a European saint of the early Middle Ages. And as in those earlier times, incredible results followed. The local Roman Catholic vicar apostolic was soon describing “a whole people who, having destroyed its fetishes, invades our churches en masse, requesting Holy Baptism.”

Although the mission spawned “Harrist” churches that survive today, Harris himself had no time for denominations, and he warned his followers that they should wait for godly preachers who would follow him. Decades later, newly arrived Methodists were delighted to find the old converts pouring into their newly founded churches.

Earlier missionaries had introduced Christianity, but Prophet Harris offered it anew in African style and tried to lift his people above divisions of race and power, violence and tribalism. When later travelers visited the region, they heard old Harris followers recalling him lovingly: “He taught us to live in peace.”