The Bible plus: The four books of Mormonism

A Latter-day Saint friend of mine once invited an evangelical coworker to church. The coworker found much that was familiar in the LDS service: hymn singing, an informal sermon style, robust fellowshiping and scripture-driven Sunday school. But then came the moment when the Sunday school teacher, after beginning with Genesis, said “Let’s now turn to the Book of Moses” and began reading: “The presence of God withdrew from Moses . . . and he said unto himself: Now, for this cause I know that man is nothing, which thing I never had supposed.’” I am told that the visitor reflexively searched through his Bible before he realized that he’d never heard of such a book, though of course the story of the burning bush was familiar. And while he didn’t mind the sentiments expressed in the words he’d heard, he knew that they were not in his Bible.

This mix of the familiar and the strange is a common experience for any who have spent even minimal time with the Latter-day Saints. The greatest contributing factor to this mix is Mormonism’s dependence on and sophisticated redaction of the Bible. All of Mormonism, even its most unfamiliar tenants, rests in some element of the biblical narrative. Academics would explain this in terms of intertextuality, noting that the meanings of Mormonism, even its unique scriptures, are achieved within the larger complex of the Christian canon. You don’t need to be a scholar to recognize this. You need only open and read the first words you see in any one of Mormonism’s unique scriptures.

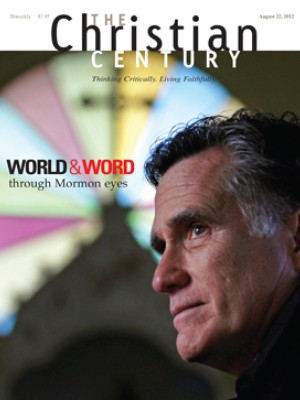

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

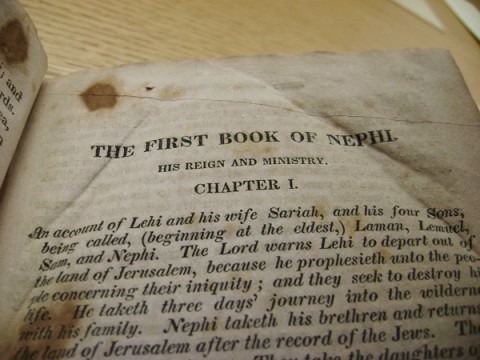

The Latter-day Saint canon consists of four books: the Bible and three other texts—the Book of Mormon, the Book of Doctrine and Covenants and the Pearl of Great Price. Each reads very much like the Bible in type and breadth of thematic concerns and literary forms (history, law, psalm). Even the rhetorical stance of each canon is biblical: God is speaking to prophets faced with temporal crises of spiritual significance. In terms of the authority granted these four texts, all have equal weight, including both Bible testaments, as historical witnesses to God’s promise of salvation, enacted by covenant with the Israelites and fulfilled in the atonement of Jesus Christ as the only begotten of the Father.

The LDS Church’s confidence in the authority and historicity of the Bible is mitigated only by scruples regarding the Bible’s history as a book. The Bible is “the word of God insofar as it is translated correctly.” The other three Latter-day Saint scriptures are also believed to be historical witnesses to God’s promise of salvation. Considered translations by or direct revelation to Joseph Smith, the church’s founding prophet, they are considered correct in their representation of God’s will and word, though they possibly contain flaws resulting from “the mistakes of men.” What follows is a brief description of these three texts and a few examples of how they reshape Christian tradition and influence Latter-day Saint belief and practice.

The Book of Mormon is the narrative of a prophet-led people’s experience with God over a thousand-year period, beginning with the flight of two Israelite families from Jerusalem in the sixth century BCE on the eve of Babylonian captivity. The people of God eventually create a complex civilization in the Western Hemisphere. The story is a cautionary tale of cycles of conversion and backsliding. It concludes in approximately the fourth century CE with an account of wickedness and consequent destruction. The climax of the narrative occurs midway with the appearance of Jesus Christ immediately after his resurrection to a chastened remnant in the Americas who are taught by him to repent, embrace the gospel and establish a church. Thus, the Book of Mormon not only echoes the narrative style and certain contents of the Bible, such as the Beatitudes, but also functions as second witness to the Bible’s testimony that Jesus is the source of salvation for all.

The Book of Mormon clearly deviates from Christian tradition by not limiting Christ’s ministry to a particular people and time. The rejection of such limitations is one of the book’s main points. The claim that “we need no more Bible” is made the object of God’s rebuke: “Know ye not that there are more nations than one? . . . because that I have spoken one word ye need not suppose that I cannot speak another.” Clearly, the Book of Mormon’s purpose is not only to second the biblical witness but also to evidence the ongoing revelation of the gospel. Notwithstanding its orthodox representation of that gospel, the Book of Mormon takes a position on certain historic theological questions. For example, while teaching the reality and catastrophe of the Fall, the prophets of the Book of Mormon reject notions of human creatureliness and depravity. Humans are not utterly foreign to God’s being. They are inherently made capable of acting for good, though only through Christ’s sacrifice is this capacity liberated from the enslaving effect of the Fall on human will. It is “by grace we are saved after all we can do.” Thus in Mormonism God’s economy of salvation is broad, though not universal in its promise of glory. Humans are prone to sin, free to reject grace and may fall from grace. Nevertheless, grace is freely given to those who in faith repent.

The LDS Church’s third canonical text, the Book of Doctrine and Covenants, is composed of revelations received largely by Joseph Smith between 1830 and 1844. Essentially a book of order and doctrine, it is the most discursive of the church’s scriptures. Again, much is familiar to non-Mormons, such as believer’s baptism, confirmation through the laying on of hands for the gift of the Holy Spirit, and affirmations such as “justification through the grace of our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ is just and true. “ Less conventional but still acceptable is the book’s emphasis on sanctifying endowments of heavenly power “through the grace of our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ . . . to all those who love and serve God with all their mights, minds and strengths.” For example, the D&C contains a version of the catalogue of the gifts of faith in 1 Corinthians, all of which are embraced within Mormonism.

LDS Church offices, too, are initially familiar: deacon, teacher, priest, elder and bishop. But the church’s charismatic offices, such as high priest, apostle and prophet, are unfamiliar in a modern context. Particularly indicative of the canon’s sanctification of the Christian life is the D&C’s provision for an ordained priesthood of all believers authorized to perform every ordinance as well as all pastoral and preaching duties.

The D&C contains a number of teachings, especially related to temple worship, that are unique to the Latter-day Saints. Space permits discussion of only one: saving ordinances, such as baptism and confirmation, performed not only for the living but also by proxy for the dead. D&C 124 describes this practice and provides a good illustration of the way in which the LDS Church’s canon leverages biblical concepts to create beliefs outside the tradition as if from within it. This text explicitly roots baptism by proxy for the deceased in Matthew 16’s reference to authority that can “bind” heavenly possibilities by earthly acts. It further grounds the doctrine in 1 Corinthians’s rhetorical question: “Now if there is no resurrection, what will those do who are baptized for the dead? If the dead are not raised at all, why are people baptized for them?”

D&C 124 claims that the answer to Paul’s question comes as deeply from within the tradition as does the question itself. First, it refers to Malachi’s promise that Elijah would come to “turn the hearts of the parents to their children, and the hearts of the children to their parents.” Smith claimed that Elijah had returned in 1836 to restore the heavenly keys to such a turning of hearts, an event recorded in D&C 110. This turning—or, as Smith termed it, binding—of the generations by sanctifying covenants with God animates the church’s genealogy program, as well as its practice of sealing marriages for eternity.

Second, the biblical imperative of Hebrews 11 is cited in D&C 124 to show the necessity of this sacramental work on behalf those who died without the gospel: “For their salvation is necessary and essential to our salvation, as Paul says concerning the fathers—that they without us cannot be made perfect—neither can we without our dead be made perfect.” Though Latter-day Saints believe that the deceased may reject grace and nullify the sacraments performed on their behalf, providing the option is the duty of the faithful to those who were without the gospel in this life.

Innumerable examples can be given of Mormonism’s canonical similarities and dissimilarities with traditional Christianity. By employing both biblical forms and hermeneutic, Latter-day Saint scripture is profoundly adaptive of historic Christianity’s theological traditions. To fully understand this phenomenon, however, one more aspect of Mormonism’s extended canon needs to be considered. Notwithstanding the D&C’s tendency to discourse, the most powerful force at work in Latter-day Saint differentiation is the narrative function of its canon. The Pearl of Great Price is the obvious case in point, though in a more subtle way it is true of the Book of Mormon as well.

The Pearl of Great Price is a compendium of several writings attributed to Joseph Smith’s revelatory powers. The two largest portions are called the Book of Moses and the Book of Abraham. Both books include a retelling of the creation story. Most significantly, this retelling includes an event before creation in which God met with his children regarding the next step in their existence. This step required the gift of more expansive powers of agency in order to learn by experience to distinguish good from evil, thus enabling human progress to higher levels of being.

The event is characterized by two contrasting concepts of how earthly existence should be ordered. The contender for one concept insisted on the use of force to ensure that humans made the right choice. The other advocated God’s original plan that offered salvation from wrong choices through sacrificial atonement. This advocate further agreed to be the sacrifice, leaving the glory to God. As you no doubt have guessed, the first contender is Lucifer, who rebelled against God, lost whatever light his name suggests and became the devil. The second petitioner became God’s only begotten son, and by virtue of his redemptive power became in all ways like God the Father.

God’s challenge to Job’s memory and his call to Jeremiah, as well as Isaiah’s lament and Paul’s dictum in Romans, may supply biblical evidence for the premortal existence of humankind. But canonization of a Bible-like narrative that directly counters the theological tradition of creation ex nihilo is one of the most provocative aspects of Mormonism. Some non-Mormons have been so provoked as to accuse the Latter-day Saints of believing the devil is a brother of Jesus in the sense that they share the same nature and power. This could not be further from the church’s canon and teachings regarding the divinity of Christ. Regardless, the belief that sacred history extends to a premortal existence for human life and to events before creation has a definitive affect on Mormons’ self-understanding and their sense of time and eternity. It is fundamental to their answer to the classic existential question, Where did we come from?

The two other questions that preoccupy religious thought are why are we here and where are we going, and the Saints’ extended canon tackles these questions as well. As noted by the Sunday school teacher mentioned earlier, the Pearl of Great Price contains an account of Moses’ theophany on Mount Horeb. The prophet is depicted as having been amazed at his nothingness after being shown the earth and its inhabitants. But he is not so dumbfounded that he fails to ask God why these creations exist, and he receives this answer: “There is no end to my works, neither to my words. For behold, this is my work and my glory—to bring to pass the immortality and eternal life of man.”

This short verse defines God in terms of his capacity to “bring to pass” or engender in his children the quality of the life he possesses—“immortality and eternal life.” The verse contravenes centuries of Christian theological anthropology that insists there is an unbridgeable ontological gulf between God and humankind. Or, in more technical terms, traditional Christianity teaches that God’s nature is fundamentally unrelated to human nature—the one uncreated, the other created. The Latter-day Saint canon asserts to the contrary that God is best understood by his fundamental relatedness, his fatherhood.

The effect of this view on the Latter-day Saints’ identity is probably immeasurable. They believe that God has known them, as he said to Jeremiah, before they were in the womb and that they are, if faithful, predestined for glory in Pauline terms. When things get tough, as in the case of Job, the Saints are to remember the time when “the morning stars sang together” about what they believe was a loving Father’s plan for their ultimate glory. On the basis of these alternative accounts of creation and Moses’ theophany, Latter-day Saints believe that the truest measure of God’s greatness is his generativity, not his sovereignty or prescient omniscience that predestines outcomes. Thus, when they voice their Christian perfectionism in terms of becoming like God, Latter-day Saints are not aspiring to power over others. As we have seen, the primordial event in their canon’s salvation history uses Lucifer’s fate as a warning against such aspiration. Rather, they understand their divine potential in terms of parenting, even the promise of an endowment of sanctifying grace that enables the faithful to facilitate spiritual, not merely physical, birth. To obtain such generativity is, for Latter-day Saints, why humans exist, and it constitutes the deep doctrinal stratum of what is typically seen as merely a sentimental attachment to family.

As for the third existential dilemma—where we are going—Latter-day Saint scripture elaborates on John 5 and 1 Corinthians 15 to affirm a variety of degrees of glory to which virtually all of God’s children will be raised after judgment. D&C 76 is the most complete discourse on this subject, and it incorporates the Pauline metaphors of sun, moon and stars to describe the varieties of glory in the afterlife. The effect is, in part, to counter the idea of a one-size-fits-all heaven capable of accommodating the varieties of human desire and action. Rather, it is hell that lacks diversity, accommodating only “those sons of perdition who deny the Son after the Father has revealed him . . . crucified him unto themselves and put him to open shame.” The rest of humanity “shall be brought forth . . . through the triumph and the glory of the Lamb, who was slain, who was in the bosom of the Father before the worlds were made. And this is the gospel, the glad tidings.” Thus, in Latter-day Saint eschatology there are many degrees of glory or “mansions” (to use John 14 KJV, since it better conveys the idea of glory than does the NIV’s “rooms”), but hell is an undiversified site with a narrowly defined population. As a consequence of these scriptural differences, Latter-day Saints do not judge religious differences as meriting consignment of people to hell, nor do they threaten nonbelievers with such a fate.

Narrative remains the preferred method of conveying Latter-day Saint teachings, however—even in eschatological matters. D&C 138 contains an account of Christ’s visit to the world of spirits mentioned in 1 Peter. It describes Christ being greeted joyfully by the righteous who had been waiting for the day of his triumph over death. But the focus of the story is on Jesus’ concern for the unjust, who also awaited their fate, and on how he chose “from among the righteous . . . messengers, clothed with power and authority, and commissioned them to go forth and carry the light of the gospel to them that were in darkness, even to all the spirits of men; and thus was the gospel preached to the dead.” This passage clearly relates to the Saints’ sense of duty to prepare for the possibility that some will accept the gospel after death. But more significantly, for believing readers D&C 138’s elaboration on 1 Peter satisfies questions about God’s justice in a world where few have known of Jesus and many are so burdened by temporal cares that they cannot hear his message. Ultimately, these two sections of the D&C, coupled with the expanded canon’s expansive view of the scope of the atonement and the power of Christ’s resurrection, are a source of great personal assurance to the Saints about everyone’s destiny because God’s saving work is ongoing.

Each year in a repeating four-year cycle, one of these canonical texts is the subject of the LDS Church’s Sunday school curriculum for youth and adults. Members are expected to read the designated scripture from beginning to end. Each book of scripture is considered as essential as any other, though the Bible is given two years of this cycle, one for each testament. The Book of Moses and the Book of Abraham are treated seamlessly within the Old Testament curriculum, as was done the day my friend brought his coworker friend to class. There is no canon within a canon—only a single history of God’s efforts to be heard in all places and by every generation.

Mormons are not theologians or even particularly doctrinaire; they are primarily narrativists. They inhabit the world of the book. They read themselves into the salvation history it tells and orient themselves to the horizon created by its promises. In sum, Latter-day Saint scriptures play a definitive role in the lives of believing readers, informing them of who they are in relation to God, why they are here and where it is possible for them and their loved ones to go. In respect to this world and the next, the Saints’ scriptures give them a distinctively positive sense of human potential based on God’s capacity and desire to save them and everyone else, as it says in the Book of Mormon, “through the merits, and mercy, and grace of the Holy Messiah.”