Unsettled issues: The Protestant-Catholic impasse

Protestant and Roman Catholic Christians recently celebrated Easter, the most important festival of the Christian year. But they did not celebrate it together—at least not at the level of shared communion.

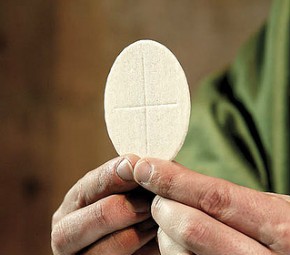

Protestant Christians who show up at a Catholic Easter mass would be welcomed, invited to sing the praises of a common Lord and expected to share in a common ecumenical prayer life. They would even be offered a special blessing by the parish priest at the altar rail. What they would not be offered is the same consecrated host offered to the Catholic faithful.

The broken communion evident at any eucharistic service, Catholic or Protestant, is an outward and visible sign of an inward and invisible state of affairs. As we draw near the 500th anniversary of the Reformation—generally regarded to have begun in 1517—it’s clear that while Catholic and Protestant churches have made enormous progress toward unity and have forged agreements over vexing issues once regarded as church-dividing, they still have much unfinished business to transact. And some of the unresolved issues that stand in the way of full communion are likely to be uncommonly difficult to resolve.