‘Tukutendereza Yesu’

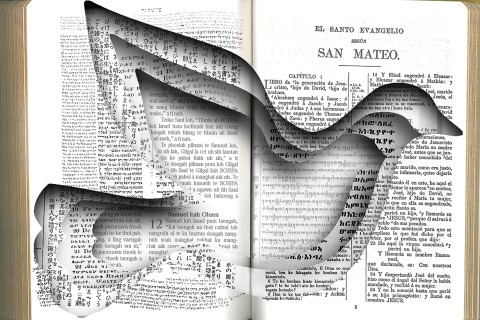

I'm never convinced when Protestants claim to be people of the Bible alone. They are people of the Bible and the hymnbook, and the two volumes complement each other splendidly. As you sing, so you believe and so you pray—and so you learn much of your theology.

As Christian churches grow around the world, it is not surprising to find an astonishing efflorescence of hymn composition. We must avoid the loose term hymn writing, as so many of the creators are primarily oral artists, and only gradually do their works find their way into written form. But however they are made, the sheer abundance and quality of those hymns is overwhelming, whether in Yoruba or Swahili, Tamil or Zulu. Arguably, we live today in the golden age of Christian hymn-making.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Trying to understand emerging Christian cultures without some knowledge of those compositions is like trying to tell the Anglo-American religious story without referring to "Amazing Grace" or "The Old Rugged Cross." And as in the English-speaking world, hymns do not stand solely on the artistic merit of their words and music. To hear great hymns is to be drawn into a familiar story, which in its way forms part of an epic mythology. "Amazing Grace" is powerful in its own right, but it becomes vastly more so when it evokes for the hearer the larger story of former slaveowner John Newton, with its legend of loss and redemption, of national sin and heroic activism. Great stories produce hymns, which in turn shape lives and drive movements.

The newer Christian world, too, has its legendary hymns. Few are as potent as "Tukutendereza Yesu," the mighty Luganda song that since the 1930s has been the anthem of evangelical faith across East Africa, especially for the pious Balokole, or the Saved. The hymn grew out of a revival that emerged in Uganda and Rwanda and which subsequently transformed churches in Kenya and further afield. It is the music heard at the region's frequent revival meetings and crusades, for the words mark the believer's acceptance of Christ. The hymn is a staple of Kenya's booming Christian music industry, and it is featured in up-tempo gospel videos. Across modern East Africa, "Tukutendereza" is hard to avoid.

But just why is it so successful? The words seem conventional enough as an expression of evangelical faith: "Tukutendereza Yesu / Yesu Omwana gw'endiga / Omusaigwo gunaziza / Nkwebaza, Omulokozi" (We praise you Jesus / Jesus Lamb of God / Your blood cleanses me / I praise you, Savior). But we have to remember the setting—a society in which animal sacrifice remains commonplace and in which people have a deep appreciation for the value of the blood that is the life. In such a setting, concepts of atonement and sacrifice have an intuitive power that they lack in the modern West. Is it any wonder that evangelical faith, with its central notion of being saved in the blood, has exercised such appeal across modern Africa?

In turn, total dedication to the blood of Christ forbids believers from being drawn into militias or secret societies that enforce loyalty by paths based on blood and sacrifice. Those who sing "Tukutendereza" accept only one sacrifice, that of Christ alone, and that faith has repeatedly caused them to suffer violence at the hands of brutal oppressors—whether the Mau Mau guerrillas of the 1950s, the Idi Amin regime of the 1970s or the more recent Lord's Resistance Army. Each such episode has enriched the ever-growing narrative associations surrounding the hymn, as stories tell how martyrs went to their deaths singing the hymn, or how hearing it softened the hearts of persecutors.

After Amin's forces murdered Anglican archbishop Janani Luwum in 1977, singing "Tukutendereza" became a quiet act of resistance to the regime and an affirmation of human rights. (Luwum himself was a loyal member of the Balokole).

Watching the triumph of a hymn like "Tukutendereza Yesu" and its many modern counterparts makes us question the dismissive view often heard in the West about the weak theological underpinnings of Christian belief in the newer churches—the idea that African Christianity is a mile wide but an inch deep. We might draw a close analogy to the 18th-century revivals in Britain or America, when immersion in the great hymns of Whitefield and the Wesleys more than made up for the lack of formal theological education among ordinary believers. The popular religious music of that time created a faith a mile deep, much as the modern hymns are doing in churches across Africa and Asia.