A world with no boundaries

Russian writer Ludmila Ulitskaya’s stories of love and defiance escape the plane of realism.

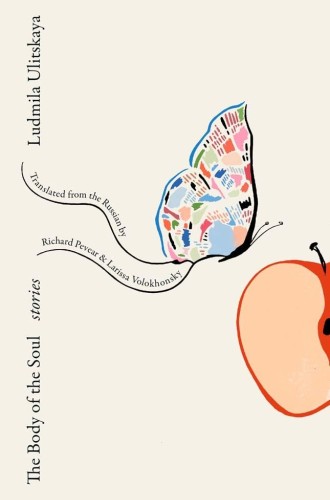

The Body of the Soul

Stories

Ludmila Ulitskaya is a badass. She is a Russian short story writer, playwright, and novelist who was born in the Ural Mountains and became a genetic scientist. Fired from the Vavilov Institute of General Genetics in 1970 for distributing underground literature, she began her literary career several years later at the Hebrew Theatre of Moscow. Her first short story was published in 1990, just as the Soviet Union’s perestroika reforms were transforming the landscape she inhabited. Her work often perceives and subtly visits the boundaries between Judaism, Christianity, and Islam—three religions that powerfully shape Russian and post-Soviet realities but are rarely discussed except as conflictual. Since the fall of the Soviet Union, Ulitskaya has lived internationally—at various times in Israel and Italy and, since March 2022, in Berlin. Two days after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, she published an op-ed in the newspaper Novaya Gazeta in which she wrote, “Pain, fear, shame—this is what I feel today.”

Now 80, Ulitskaya is writing fearlessly and with mature depth. On the surface, her new stories have a plainness that is reminiscent of Chekhov. They almost always begin in a realist frame. Alisa, an engineering draftsman, installs a bathtub. A busybody woman tries to arrange a marriage for her accountant daughter. Zhenya buys a pair of unique walking shoes for which she does not have the name, moccasin. Most of the stories take place in a time period between an insulated Soviet Union and an emerging capitalistic and global reality.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

In nearly every case, something happens to twist the realist framework and take the story onto a different plane. At the beginning of the book, the shifts are subtle and somewhat familiar: love disrupts characters’ well-laid plans, or death reveals long-held secrets. But as the book traces the route from body to soul, magical realism enters the picture. Characters talk with the dead. They leave their bodies and visit long-abandoned places. One character becomes a butterfly.

In the first story, we meet Zarifa, an Azerbaijani woman, who is married to Musya, an Armenian woman. Already we are on ground that is rarely broken by short stories in the Russian tradition. Ulitskaya’s eye draws us to the margins, to the untold and unsung. She is not interested in narratives about Russian greatness or the Russian soul. Instead, she finds subjects and means that disrupt these dominating discourses—through the singular bodies and souls of ordinary people. She especially loves the stories of middle-aged and older women, another realm rarely traced in literature. Her characters are often people who have already given up on life, been severely disappointed by it, and cannot imagine new futures for themselves, until . . . . (Ulitskaya loves the ellipsis.)

And love is the central thing to keep in mind. Ulitskaya hints at her purposes in a Whitmanesque, lyrical introduction entitled, “I Need No Others . . .” It begins, “Amazons, my girlfriends, young and old, / in varicolored boots, galoshes, sandals, barefoot, / in a chain dance, singing, carefree, tramlike, noisy, sometimes shrieky.” She goes on to describe the lives they’ve lived together, carrying potatoes, enduring KGB searches, stealing each other’s husbands, supporting each other through abortions. “I need no others, I love these ones . . . / I need you the way you are—and I myself am the same,” she concludes.

In other words, these stories are acts of love and defiance. They demand that the reader see differently, feel differently, leave the known for the unknown, and enter landscapes of love and desire they have not previously considered. The Body of the Soul can be read in one sitting. Its stories flow seamlessly from one to the next, each satisfying in its own way but also part of an increasingly evident whole.

In the final story, a bibliographer named Nadezhda Georgievna begins to lose her connection with words. The first word she forgets is serpentine, and eventually her memory for everything disappears. Even as her world recedes, another opens: a “radiant world [that] had no boundaries. It moved, developed, expanded, and unfolded like a serpentine road.” This is the world Ulitskaya invites us into, where our limitations become opportunities and our failures are loved beyond measure, where there is always more than meets the eye.