When Judaism became Judaism

Archaeologist Yonatan Adler argues that widespread, ordinary observance of the Torah did not take place until the Hellenistic period.

Yonatan Adler posits a convincing thesis, tightly and compellingly argued, that widespread observance of Pentateuchal legislation by Judeans—or what we now call Judaism—emerged no earlier than the Hellenistic period. Surveying textual and archaeological evidence from the first century CE (when recognizable Judaism was at its Second Temple peak) and working backward, the archaeologist concludes that what we now recognize as Judaism arose in response to Hellenism, as a negotiation of the extent to which Judeans conceived of their common ethnicity by reference to a set of common ancestral customs based on the redacted Pentateuch. This happened, Adler argues, under the 80-year rule of the Hasmonaeans, a family whose members are widely recognized as the last leaders of an independent Israel before Judea became a client state of the Roman Empire in 63 BCE.

In his exploration of what are now quintessentially Jewish customs—following dietary and ritual purity laws; avoidance of figural art; circumcision; observance of sabbath, Passover, Yom Kippur, and Sukkoth; use of the seven-branched menorah; and use of synagogues—Adler shows we have no evidence that any of these practices existed before the Persian period. In fact, he argues, we have both textual and archaeological evidence to the contrary. For example, while images of God are clearly prohibited from the later Hasmonaean era onward, they are present in the Judean archaeological record before the Persian period and frequently referenced in the Hebrew Bible beyond the Pentateuch.

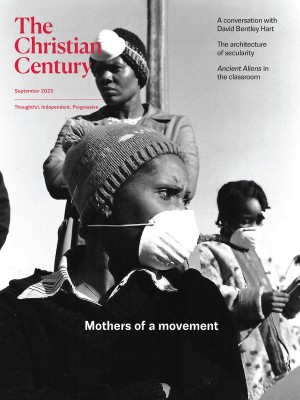

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Adler does not challenge the ideas that the literary sources of the Pentateuch are all preexilic, that their redaction did take place in the exilic era, and that some groups from preexilic Israel and Judah practiced some of the legal codes that compose the Pentateuch. Nevertheless, he insists, the widespread, ordinary observance of the Torah as law for all Judeans—comprising a distinct sense of “Judaism” or “Jewishness”—did not take place until the later Hasmonaeans adopted these preexisting traditions and texts as the norm for everyone. The goal behind this shift, Adler posits, was to launch a program of cultural unification to establish Judean distinctiveness in the Hellenistic world. Isolation was not the goal, it’s important to note, because the Hasmonaeans themselves were very much Hellenistic monarchs and Judean life was irreversibly Hellenized by this point.

Adler’s argument joins a rising chorus of recent scholarship to this effect, including the work of Shaye J. D. Cohen, Reinhard Kratz, and John J. Collins. These scholars have stressed that the lifeways of ancient Israel and Judah coexisted with postexilic “Judaism,” that the concept of Judean identity predicated on the Mosaic Torah circulated for several centuries as a marginal position before it was adopted as the formal rule of Judean life, and that alternate concepts of Judean life and theology to those espoused by the Mosaic Torah continued to exist even after its widespread adoption.

Ancient Israel and Judah before Adler’s chosen period and the postbiblical rabbinic Judaism that emerged after it are, in fact, defined by legal and ideological pluralism. Contemporary scholars assume that ancient Israel and Judah only gradually came to think of themselves as such, and that the authors of the Hebrew Bible (before, during, and after the exile) spoke from the perspectives of an elite scribal minority on their national legacy long before they spoke to a widespread geographic people committed to some degree of its study and implementation. Likewise, rabbinic exegesis was a schoolhouse affair long before it became the normative legal position of the majority (but never the totality) of Jewish communities in the Middle Ages.

Adler, in other words, supplies a welcome and intuitive addition to our evolving sense of what “Judaism” was in antiquity and how and why it came to be that way. He provides, therefore, a crucial step in understanding how Judaism came to be the vibrant, pluralistic ethno-religious culture that it is today.

I read this book as a Christian and therefore a member of a tradition whose precedent is in a Judean sect of Judaism which centered on an apocalyptic and messianic community headquartered in Jerusalem with diaspora and gentile membership. This precedent tradition accepted the Mosaic legislation as normative for its Judean membership. While this is not Adler’s primary concern, I am interested in the way that his thesis might shape how Christians read one of the central constellations of questions confronting early Christian writers: how to include gentiles in a Judean movement about the Judean messiah, whether they must embrace full Torah observance for inclusion, and to what extent community between Judeans and non-Judeans in the movement is possible or desirable.

As Adler would have it, under the Hasmonaeans, the possibility of becoming a Judean by ritual circumcision emerged as a way for a non-Judean to join the nation, whether voluntarily or forcibly. The Hasmonaeans enacted a campaign of the latter toward local people in their region, most infamously among whom were Herod’s ancestors. For Paul, though, gentiles had no need to adopt the ethnic law of Judeans, as God’s goal was not to Judaize them but to reconcile them through ethical monotheism and submission to God’s Messiah, Jesus.

Paul explains his pluralistic concept of divine expectations in 1 Corinthians 7 partly by appeal to his apocalyptic eschatology. With the time being so short, there’s no point in seeking a lifeway change so drastic as circumcision and conversion (if one is non-Judean) or abandoning the divine gift of the law (if one is Judean). The eschatological unity of all in Christ at the resurrection and metamorphosis of the dead will render these ethnic distinctions irrelevant in the imminent kingdom of God.

It is not hard to see, though, how this position on gentile inclusion sans conversion may have inadvertently opened the door to the history of Christian persecution of Judaism. For most Jews today, the question of how to relate to Christianity is not simply characterized by theological possibilities. Instead, it is characterized by two millennia of Christian persecution, soft and hard; by the names and memories of ancestors who were harassed and assimilated and exiled and killed by Christians; by the not so historically distant reality of official Christian teachings of Jewish obsolescence.

Christians are often unconscious of this because they habitually think of Judaism as a religion and Jewish people as adherents of that religion rather than thinking of Jews as a people group or a nation—an ethnos, with ancestral practices and beliefs that have become normative over time. Theses like Adler’s can help correct this misunderstanding by helping Christians to see that while Jewish people are not reducible to Judaism, it is not possible to distinguish anti-Judaism from antisemitism.

Conversely, in an age after Christendom, when Christian forms of belonging, behavior, and belief are in rapid decline, this history also forces Christians to ask: What are we? This leads to a final observation about Adler’s thesis as it pertains to the dynamism of biblical law and literature for Jews and Christians. Historical criticism simply does not support the originalist reading of the Bible as a passively received corpus of texts and other practices to be uncritically obeyed or propositions to be simplistically believed; ditto for the postbiblical tradition of commentary and interpretation.

Consistently, from their earliest recorded history, Jews and Christians have been dynamic readers of their practical and textual inheritance, adapting to new situations and information, reading with their own moral consciences and experiences as core players in the interpretive task, seeking to construct resilient and meaningful communities rooted in the past but oriented toward the future. A lesson from Adler, then, might be that Christians do not have to seek return to previous forms of Christianity as a strategy of renewal. They can return to ancient sources and produce new syntheses, just as the Hasmonaeans, the Pharisees, Jesus, the apostles, the rabbis, and early Christians all did.