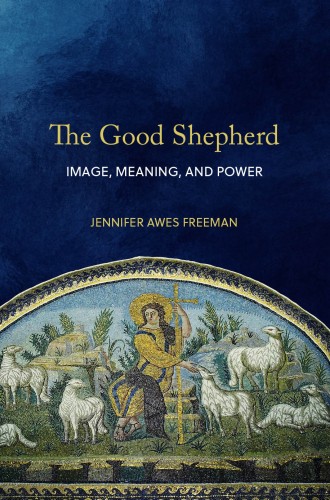

The Precious Moments website advertises a popular Easter collectible that features a young girl with teardrop eyes, dressed in a white lamb costume, clasping a shepherd’s staff, and gazing up lovingly at Jesus. Similarly, prints of Warner Sallman’s placid, lily-white painting The Lord Is My Shepherd still sell well on the internet. Such kitsch, Jennifer Awes Freeman notes, seems a far cry from the Babylonian stele, featured at the Louvre, which depicts the lawgiver, military hero, and ruler Hammurabi (c. 1810–1750 BCE) as “shepherd of the people, whose deeds are pleasing to the goddess Ishtar.”

Centuries of sentimentality have cloaked the potency of an icon whose roots stretch back five millennia. In a masterful historical study, Freeman, who teaches theology at United Theological Seminary of the Twin Cities, traces the career of the good shepherd motif through pottery, funerary art, sacred texts, treatises, and church mosaics in a narrative span that ranges from ancient Akkadians in the Near East to the Christian Middle Ages in Europe. This bucolic figure, she shows, has been used by priests, prelates, and kings to inscribe and legitimize their power—even when such elites had very little direct contact with actual living shepherds.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Even critical scholarship, she argues, has been ignorant of the multivalent, supple versatility of the shepherd icon. This is especially true of historians, who contrast too cleanly an early pacifist church with the post-Constantinian religion of establishment.

The Hebrew Bible idealizes David as the paradigmatic shepherd-king. In 1 Samuel 17, the boy spurns Saul’s clunky armor and sword for the shepherd’s weapon of choice: a simple sling and a few stones. “It was the defensive and combative nature of shepherding that prepared David for battle with Goliath,” Freeman writes. David’s rule over a united Israel, fraught as it was, serves as the model by which prophets (and later biblical historians) judge subsequent rulers. The Bethlehem-born shepherd-king harkens back to earlier figures. Abraham guides his flocks, both animal and human, into Canaan. Moses abandons the sheepfolds of Sinai to liberate his people from Egyptian bondage.

Biblical heroes evoke the broader context of the ancient Near East, although how the figure was inscribed varied across cultures. The ancient Greeks, for example, viewed their shepherd-rulers more equivocally, illustrating their more realistic view of their fallible leaders. Homer’s epics include hundreds of allusions to metaphorical shepherds, from the raging Achilles, whose sword is lavishly engraved with pastoral scenery, to the bad shepherd Paris, whose folly brings destruction upon his native Troy. The shepherd-kings of the Greco-Roman era combined elements of divinity, philanthropy, violence, and safe passage to the afterlife, as ruling classes safely segregated from actual shepherds continued to romanticize pastoralism.

Ancient Christians both appropriated and critically modified the good shepherd paradigm. Jesus names himself as the “good shepherd” who “lays down his life for the sheep’’ (John 10:11), as well the sheep’s gate, while elsewhere John also presents Jesus as the paschal lamb who gives his own life for his people. Jesus paradoxically embodies “power in powerlessness,” Freeman writes. For early Christians, the good shepherd embodied both the unity of and the difference between the two testaments, while shepherd iconography abounded in funerary art, providing reassurance and hope of safe passage to early believers facing martyrdom.

After Christianity became officially established in the fourth century, political leaders still were seen as bearing the shepherd’s mantle, if sometimes ambiguously. Eusebius lauded the “noble shepherd” Constantine I, whereas Ephrem the Syrian denounced the “bad shepherd” Julian the Apostate as “a duplicitous wolf in sheep’s clothing.” In later antiquity, the shepherd figure was increasingly uncoupled from political rulership and applied more narrowly to pastors and church leaders. Gregory the Great’s monumental sixth-century Pastoral Rule identifies the ideal shepherd as a seasoned ascetic who defends truth and protects the faithful from heresy. Strikingly, this good shepherd embodies a Christlike humility evoking loving imitation.

Over time, the good shepherd icon imagery faded from the realm of visual arts (although it remained a typical figure in sermons and treatises) and was increasingly supplanted by the paradoxical Agnus Dei, the sacrificial slain lamb-as-ruler. “Whereas the imperial shepherd governs a flock of citizens with the goal of subordination and control, the ecclesial shepherd guides reason-endowed sheep in his image, and ultimately, in that of Jesus,” Freeman writes. The panoramic apse in the sixth-century Basilica of Saints Cosmas and Damian in Rome depicts the lamb ruling from a rock.

By the Fourth Council of Toledo (633 CE), the image of the bishop’s crozier emerged as an emblem of protection and correction. The severing of the shepherd symbol from monarchical rule continued into the Carolingian period in the ninth century, although Charlemagne himself was depicted as a “pastor” like David. Increasingly, the good shepherd in image and text was applied more exclusively to Jesus himself and to the church leaders who modeled his spiritual authority.

The good shepherd was a common image in early Christian funerary art, as well as in baptism, which included recitation of Psalm 23. In a book that is well suited for seminary classrooms or parish study, Richard Briggs, an Anglican priest and Old Testament scholar at Durham University, explores the good shepherd image within his theologically and pastorally oriented exegesis of this most beloved of texts. The 23rd Psalm, Briggs shows, helps personalize the figure of a divine good shepherd and inspires trust in God’s loving providence. Its imagery not only resonates in hymnody and praise music but also echoes in such contemporary songs as Coolio’s “Gangsta’s Paradise.”

While showing deference to the vast literature on Psalm 23, Briggs tries to curb modern historical-critical overreach, with its typical fixation on authorship and philology. Who wrote the text, which the Hebrew original titles “a psalm of David”? The short answer is we do not and probably cannot know. Briggs assumes that the author probably was not David himself. Notions of authorship were more fluid in the ancient world than today. It’s possible that the psalm was written in dedication to the king after the Jerusalem temple was built, maybe even as late as exilic times.

Conversely, though, Briggs also criticizes well-intended works of popular devotion that at times leap past the actual text into the interpreters’ personal experiences. Intricate details about the practices of animal husbandry, ancient or modern, might do little to aid interpretation. The text’s power, he argues, resides rather in its flexibility and resilience across centuries of Jewish and Christian interpretation to inspire “confidence and trust,” amid trials and even literal enemies, “that the Lord God is concerned with me personally, as my shepherd, and that my needs will therefore be met.”

Nonetheless, in terms of its original context, Psalm 23 is best understood as a composition meant for oral recitation or singing in public worship. The proper subject of the psalm, he insists, is neither David nor any other human king. It is the God of Israel, who is also the God of Jesus Christ. Although modern research can enrich, clarify, and broaden our understanding of the psalm, Briggs writes, “I affirm: the basic contours of the traditional understanding of Psalm 23 have not led us astray.”

Like other biblical interpreters informed by such thinkers as Hans-Georg Gadamer and Paul Ricoeur, Briggs rejects a naive two-step model of interpretation as exegesis plus application. Instead, he offers a three-part exposition, focusing on the worlds of meaning behind the text (historical background and composition), in the text (line-by-line exegesis), and in front of the text (how the text continues to instruct and inspire). His introductory chapter on historical criticism, which seasoned scholars might find a bit cursory, is largely an exercise in ground clearing meant to open a space for the translation and confessional interpretation that follows. Briggs highlights a crucial literary distinction between the text’s author and the literary voice or persona it projects.

In his exegetical chapter, Briggs offers a translation remarkably close to the well-worn King James rendering, but there are key differences too. For example, in verse 3, the shepherd “restores my life” (rather than “soul”), emphasizing God’s care of physical as well as spiritual needs. Still, he retains the familiar “valley of the shadow of death” of verse 4, arguing, against some modern critics, that the dark valleys of life might at least imply actual death, whose power encroaches upon the sphere of the living even before its literal, clinical arrival—as in cases of severe suffering, threat, and illness.

The final chapter ties together the preceding sections to hone in on the challenges of preaching and hearing Psalm 23 anew in churches today, tasks that require literary sensitivity coupled with theological imagination. Following Gerhard von Rad, Briggs argues that the text itself speaks, and “the preacher is called to get out of the way.” He writes that his own pastoral ministry has confirmed that “this psalm with a minimally defined background has a maximally effective reach into new and different contexts.”

Preaching in rural Durham, he came to see the psalm as more bracing than bucolic, interweaving its message within the fraught lives of his parishioners. He once preached in Sri Lanka on the anniversary of the 1989 Velvet Revolution, and his hearers shared terrifying experiences of being tracked down, in striking contrast to the good shepherd, whose “goodness and mercy will pursue me all the days of my life” (in Briggs’s translation). Thereby, he writes, “we are called beyond our present difficulties to a vision of peace that outlasts our present darkness.”