Mary, Joseph, and a tea vendor named Sami

In Luke’s Advent story, Bethlehem’s economy is central—and it looks a lot like Bethlehem’s economy today.

My husband and I traveled to Bethlehem. My first vivid memory of the place is of Star Street, which is traditionally acknowledged as the final portion of Mary and Joseph’s journey into town. As Claude and I walked the Advent road, we were met by a local man carrying a round brass tray, offering us hot tea with a fierce and repeated insistence. Uneasy at first with his incessant hospitality, we swerved up limestone stairs to sidestep him. Later, however, we returned to sit in the alley by the blue metal door of his kiosk. We learned that his name is Sami—and that the desperate economic need we had perceived exists as part of a more complex reality.

The Bethlehemite economy has been wracked by the separation wall and checkpoints in the West Bank. These creations of the Israeli government have made it harder than it used to be for tourists to visit, stay, and spend money in the little town of world renown. Many pilgrims simply avoid Bethlehem entirely for fear of crossing a checkpoint. If they do go, they spend four hours now instead of four days, and many bring with them fears of Palestinian violence. Rushed in by tour guides only to visit the Church of the Nativity and a few select shops for souvenirs, they then board their tour bus and hurry out.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

They miss the taste of Sami’s tea, Afteem’s falafel, and fresh-squeezed pomegranate juice in Manger Square. They miss talking with the people who have stewarded holy sites with care for centuries as an aspect of fidelity to their homeland. They miss both the economic hardship that permeates the site of Mary and Joseph’s journey and the vibrant life that surrounds it.

Behind the separation wall, Claude and I were treated as guests. We experienced kindness and joy, a sort of abundance we won’t soon forget. But innkeepers need to eat, purveyors of tea have school fees to pay for their children, and shopkeepers have medical bills to settle. Mutuality is part of hospitality—along with a room and a meal we are given the opportunity to offer money that will allow for provisions for our hosts. In depressed economies, our dollars are a tangible sign of support.

Sami’s welcome was genuine; he also needed us to buy his tea. Both things were true, a common duality in stingy economies where people struggle to survive. And both reflect something of the Advent story in Luke about the overlap of uneven economies and hospitality among the poor ones, like Joseph and Mary.

The whole world, now under the control of Caesar, meets a decree to register for Rome’s census. This is the first such registration under the Syrian governor, a client ruler in the region. Everyone in the empire goes to their ancestral hometown to register. This means that Joseph has to go from Galilee south to Judea—from Nazareth to the root system of his family tree, Bethlehem—to register. Mary, in her very pregnant state, has to travel the rutted terrain with him. When Caesar speaks, everyone moves.

Luke sets the Advent scene with an unmistakable economic marker. Caesar’s census is not about demographic numbers; it is a count of livestock, crops, and potential taxpayers. It is an inventory of wealth that allows the empire to further spread the burden of taxation. A census is always bad news for the poor, never lightening their load. From time to time, though, a census is known to ignite rebellion.

In the opening verses of Luke 2, the word register or registration appears four times in quick succession. To ancient readers, this would signal a land preoccupied with taxation. Enrollment in the census to pay taxes to Rome is the immediate context of this scene. The tax initiative reaches from Syria down to Judea and from the rulers, like Caesar and Quirinius, to the ruled, like Joseph and Mary. No one is spared.

Luke doesn’t provide an exact history so much as create a picture of the world Jesus was born into: economic hardship, a reign of power. Things are tight—and they will soon get tighter as Caesar calculates the tribute owed to him and his functionaries (provincial rulers and high priests included). To refuse to pay tribute equals rebellion and invites the punishment of Roman legions. Caesar’s economy is precarious and potentially perilous for most people.

Imperial fiat: one word, a single order from a seat of power, and populations shift without recourse. Luke points with a heavy hand at the census and registration to highlight not only the economy but also migration patterns, family trees, and roots. A census is impersonal and mandatory. No exceptions, not even for a woman whose child is nearly crowning.

History does not corroborate the kind of census Luke describes, in which people were required to return to ancestral towns to enroll in order to pay taxes. Imperial administrations typically counted and calculated what they could extract. There was a census connected to Quirinius, but it occurred after the birth of Jesus. Still, Luke creates a world that mimics the dynamics he experienced, enfolding his Advent story into the bigger story of all the times God arrives into our conflicted lands and broken economies.

Beginning with the economy and ever-looming loss, Luke shows us an economic world with all its demands, exploitation, and humiliation for those at the bottom. Against this backdrop of taxation, salvation enters. And the kind of deliverance Luke suggests is one that deals with realities like the hunger for daily bread, the fear of land loss, the search for work, and the burden of indebtedness.

Joseph and Mary make their way from Nazareth to Bethlehem as the empire and its economy demand. They find long-lost family members awaiting them, and they squeeze in where they can. Neighborhoods surge with the influx of relatives coming to register, and every corner of every house hosts someone. Bethlehemites work to make room for everyone—Joseph and Mary are no exception. Some of the families returning now have not been here since the Babylonian exile, after which their ancestors settled in northern villages such as Nazareth. This may be their first contact with southern relatives and with the landscape that was home to King David. Their excitement mingles in the air with their economic anxiety.

The travelers enter common Bethlehemite houses built like simple compounds with a series of small structures arranged around a stall where the livestock stay at night. Some covered rooms ring the stall, and beyond them are a few private, enclosed rooms where most of the family lives. There is plenty of space to offer guests. Luke describes a full house, the private enclosures full and even the covered rooms unavailable. By the time Joseph and Mary arrive, the only room available is a corner in the open stall area among the livestock, where a manger stands. Still, this is within the family compound, and inside they meet the warmth of hospitality.

Most Advent scenes misunderstand the scenario that greets Joseph, Mary, and others upon their arrival. They are welcomed by family members. We are told that “there was no room for them in the inn,” but the phrase is better understood as “there was no space for them in the usual guest room of the home.” Room would have been made for everyone, even if it was a corner here or a stable there. As long as everyone was under the same roof, it didn’t matter if they were in a private nook or on a straw mat next to the goats.

The home is bursting at the seams, but Joseph and Mary are around the table for meals, joining in the conversations among relatives. Modern notions of private spaces had no place in the ancient rubric. Every relative received a welcome, and everyone else adjusted to make it work.

Amid the bustle of family and the logistics of accommodating everyone, Mary’s water breaks. Maybe she is among the women preparing the evening meal, chopping cucumbers or pitting olives, when the cooks transform into midwives. They guide her to the corner of the stall and make room for her to lie down and for them to huddle around her for the duration of labor. Dinner can wait; the baby might not.

So Mary experiences the birth of her first child not only with Joseph to help but surrounded by mothers and midwives. She is grateful that her cousin Elizabeth arrived the day before, that she can rely on her company once again as they cross another threshold together. She draws from the wisdom of her relatives as she grips their hands. She lets out screams that startle the goats and make the donkey, still tired from the long journey, anxious.

Mary’s son—God’s son—crowns. At that moment, no one thinks of Caesar or the registration or the coming tax increase. A new life enters the world. Mary and Elizabeth think that perhaps a new kingdom has entered too. The birth of the prince of God’s peace changes the world. Against the harsh backdrop of an imperial economy, he comes into the world in the most common circumstances. He embodies the hopes of ordinary priests and farmers for true liberation; he confronts their fear that life will only get worse for them under this empire. “The hopes and fears of all the years are met” in the holy child as God takes direct action and enters the story in human skin.

Is there any hospitality on offer in Bethlehem? This is one of the conversations around Joseph and Mary’s arrival to their ancestral home and, soon after, the birth of their child. Due to poor interpretation of Luke’s test, Bethlehem and her innkeepers have historically been burdened with a bad reputation regarding their lack of welcome for the Holy Family. Fadi Kattan is innkeeper and chef at the Hosh al-Syrian Guest House on Star Street. As a Bethlehemite, he is familiar with the caricature of the inhospitable innkeeper. “It’s contrary to what I know of Palestinians,” he told me. “We are so open to foreigners and guests.” He assured me that his fellow innkeepers would never turn away a pregnant woman or any woman in distress, adding that this local practice of hospitality was shaped by the Abrahamic faith traditions.

This misreading of Luke 2, mixed with current logistical challenges presented by life behind the separation wall, makes it easy for people to misunderstand who the original witnesses to the birth of Jesus in Bethlehem might have been. They were people of the land, some of whom might have been Fadi’s ancestors. Today’s Palestinian Christians still commemorate the arrival of Joseph and Mary down the cobbled Star Street and celebrate the birth of Bethlehem’s favorite son. Jesus was born into the extended welcome of Jewish relatives and non-Jewish neighbors, living stones who bear witness to Jesus in their hometown. Fadi reminds me that this welcome continues.

In the logic of Luke’s narrative there is another scenario as well. When families were called to pay tribute, every family member helped bring in the harvest needed to pay their share. Families would spread out in orchards to harvest fruits, nuts, or olives. They’d crowd together under the generous canopy of fig trees at mealtime to share bread and sage tea. The family presence would make clear that this land was not abandoned or easy pickings for the imperial interlopers. Yes, a large portion of their bounty would be given over for taxes. But their presence somehow embodied a kind of resistance. They were still here. They could be moved by imperial decree, but not easily erased from their land.

In the Advent story, as Luke tells it, the economy matters. Attentive readers are led to understand a concrete kind of pressure, which also sets tangible contours for that expectant hope. Against the backdrop of a dangerously exploitive economy, what might deliverance look like? Debt relief? Debt forgiveness? A lighter tax burden? Ample economic resources to avoid foreclosure, to keep family land? Are these a part of God’s salvation?

Beyond our consumer-driven season’s gifts for one another, Luke calls us to a profound investigation of our economy and how it impinges on our neighbors. His text asks: Do we see who is crushed by the current economic realities? Do we understand that even our acts of charity are too thin against the demands of Advent? Because there must be more than benefiting from Caesar’s economy all year long and then giving from our extra during one short season. There must be more than deciding which people in need we deem worthy of our generosity.

A true resistance worthy of the first Advent would be a move into durable justice work the rest of the year. Imagine giving to a local food bank during Advent and then working on advocacy related to food insecurity and childhood hunger the rest of the year. Imagine learning about the realities around school lunch programs—how many need free or reduced-price lunches in your local schools; whether quality meals are offered—and organizing your community to improve what is on offer to kids. Imagine spending the year tackling the policies that create food deserts, which keep many neighborhoods undernourished. There are many other possibilities: affordable housing and tenants’ rights, fair wages, accessible health care, Indigenous land rights.

When I think of how Luke puts the economy front and center in his Advent narrative, I imagine that we are meant to do the same in our present Advent practice. How do we see the economy, who it hurts, and the injustice that riddles its structures? What do we do to come alongside the modern Josephs and Marys, forced to move to Bethlehem and suffer the modern Caesar’s unforgiving tax burden? Offering hospitality to those crushed by economic hardship, yes. But also hearing Mary’s song echo in our ears and participating in a grand reversal that feeds the hungry and dethrones those who dominate the economy for their own benefit. For Luke, the economy is no mere backdrop for the narrative; it’s a feature of deep engagement with the reality of the world God arrives to upend.

You only have to visit Bethlehem once for the notion of the inhospitable innkeeper to be deconstructed. Tea vendors like Sami, restaurateurs like Fadi, taxi drivers, and a bevy of shopkeepers along Star Street beckon visitors to come and see. They obviously have things to sell; that’s their livelihood. But this isn’t crass economics but rather a vocation of hospitality, with generations of family life sustained in similar ways. There is a warmth among Bethlehemites, an eagerness to share their beloved town with visitors and tell stories about their lives.

Claude and I checked into Hosh al-Syrian, Fadi’s small guest house carved into a limestone building from the 1700s, and finally settled into the charm of Bethlehem. “If you want the best tea in Bethlehem, stop by and meet Sami,” the innkeeper recommended. That’s how we found our way back to the insistent tea vendor mere steps away from our inn.

A tattered blue awning marked the cut-out kitchen, kettle whistling, herbs piled high. When Sami saw us, a smile overtook his face as he offered tea. He pulled out plastic chairs and a small table. “Sit, sit,” he instructed. He appeared again with glass mugs of steaming tea with rosemary, cardamom pods, and a lime wedge. He sat with us and told stories unsolicited. “My mother is Christian, my father is Muslim, but I just love everyone,” he said. And sitting in his makeshift café, listening to the dueling sounds of the call to prayer and a riot of church bells, it made sense.

Sami told the story of a man who took an interest in him over another cup of tea, upon hearing of the struggle Sami and his wife had starting their family. The man was an Israeli doctor—this was before the separation wall was built—and he responded to Sami with medical help that resulted in his wife’s first successful pregnancy. Sami’s own generous and inclusive spirit opened the door for grace to find him. He showed no partiality when it came to hospitality, and the Spirit seemed similarly inclined.

In the days that followed, Sami wove us into his neighborhood. His, our, and their stories braided together over cups of fragrant tea. As more chairs materialized, so did more people and more conversations. “Sami loves everyone,” neighbors boasted as they popped in for their daily tea. But it was equally clear that everyone loved Sami, both his smile to brighten their day and his tea creating a moment of relief from the heaviness of living behind the separation wall. Advent continues to be illuminated by one ordinary tea vendor embodying hospitality, still an act of resistance in a stingy economy.

In God’s economy, we are not nearly as powerless or invisible as imperial economies would have us think. In God’s economy, salvation includes reconsidering how our economies are structured, who they press upon, and how we can keep our communities safe and sustainable for those visiting from afar, like the Holy Family. I’ve learned about Advent from Luke, but I’ve seen Advent lived by Sami, offering small salvations wherever he can.

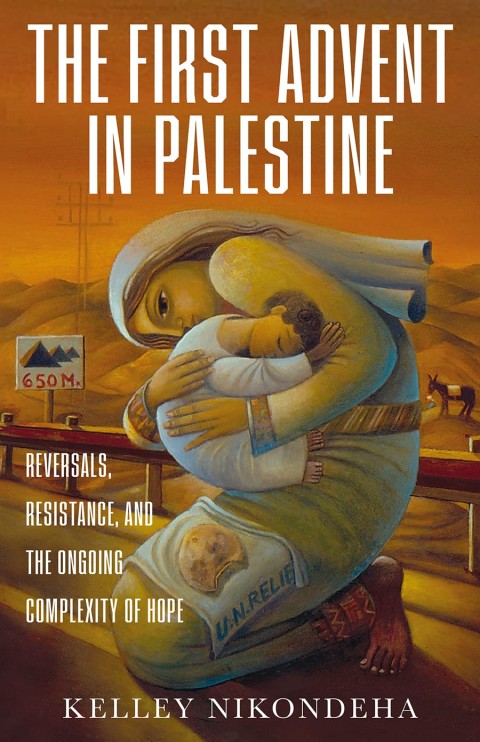

This article is adapted from The First Advent In Palestine: Reversals, Resistance, and the Ongoing Complexity of Hope, forthcoming from Broadleaf Books.

* * * * * *

Jon Mathieu, the Christian Century's community engagement editor, engages Kelley Nikondeha in conversation about her article and Luke's call for economic justice.