Sanctuary churches, cities may face legal consequences

Pilgrim–St. Luke’s United Church of Christ in Buffalo, New York, consulted lawyers before deciding to join the sanctuary movement and offer shelter to undocumented people. When it came time for the vote in the congregation of about 110 people, it was unanimous.

“No one blinked,” said Justo Gonzalez II, the church’s pastor.

The legality of congregations housing undocumented people to keep them from immigration authorities is unclear.

“We do not want to be bad citizens; we do not want to violate the law,” Gonzalez said. “But we will stand on the side of justice, and we will stand on our faith and God’s law and our understanding that we are to welcome our brothers and sisters.”

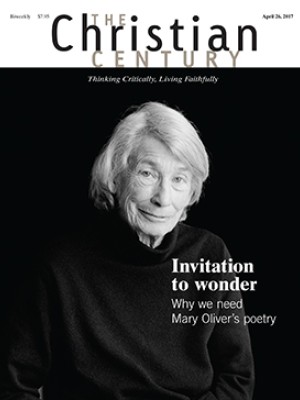

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Participation in the sanctuary movement surged in recent months, doubling from 400 to 800 U.S. congregations, according to Church World Service, which offers immigrants legal assistance and helps organize the sanctuary movement. The movement includes Christians, Jews, Muslims, Bahá’ís, Buddhists, and more.

While some congregations offer physical sanctuary, others provide funds, food, clothing, or legal assistance. But it is the congregations that shelter undocumented immigrants that take the legal risks. And that has some religious leaders preaching caution.

In Chicago, Cardinal Blase Cupich told priests that Immigration and Customs Enforcement officials may not enter churches without a warrant, yet he also reminded priests that only they may live on church property.

Bryan Pham, a Jesuit priest and professor at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles, outlined legal points churches should consider before becoming a sanctuary congregation:

- There is no legal definition or standing for a claim of sanctuary, so housing an undocumented immigrant in a house of worship is a violation of federal law.

- Congregations can’t claim that harboring an undocumented immigrant is an expression of their First Amendment right to free exercise of religion.

- Claiming a house of worship as a sanctuary and housing people inside it could be a violation of local ordinances, which may give law enforcement officials probable cause to obtain a warrant for a search and possible arrests.

- Labeling a house of worship a sanctuary “may give a false sense of safety,” Pham told National Catholic Reporter. “If you declare yourself a sanctuary, you’re implying you can provide legal and other protection. And that’s not true.”

To date, ICE officials have not entered any churches to conduct a raid, though they did stake out a church-run homeless shelter in Virginia and arrested people as they emerged. In the 1980s, some church leaders in several states who sheltered some 2,000 undocumented immigrants from war-torn Central America were tried and convicted but were not given jail sentences.

Today, immigration experts say ICE will likely refrain from entering a church—deemed a “sensitive location,” along with schools and hospitals, by the Department of Homeland Security—because the act would be a public relations nightmare.

At Pilgrim–St. Luke’s in Buffalo, the church officially opened its doors to undocumented people with an announcement in local media in February. Gonzalez declined to say whether the church is housing anyone.

“I can say, when there have been rumors of ICE activity and Border Patrol activity we have opened up the church and people have come and we have spent the day with them, fed them, and provided them a safe and sacred space,” he said.

Should ICE come to the church, its employees are ready, Gonzalez said. They have been trained in the proper protocol and their legal rights: ICE officials must present a warrant and the name of who they are looking for.

“We no longer just buzz people into the building,” Gonzalez said. “We have to know who you are and why you are here. We are doing the best we can to protect ourselves and stand firm that this is holy ground that we will not allow to be violated.”

President Trump signed an executive order to deny funding to cities that refuse to share immigration status information with ICE and to detain undocumented immigrants who commit nonviolent crimes.

Attorney General Jeff Sessions ramped up threats to sanctuary cities in late March, saying the government would take “all lawful steps to claw back” federal funding awarded to cities that do not fully comply with federal immigration enforcement.

“I urge the nation’s states and cities to carefully consider the harm they are doing to their citizens by refusing to enforce our immigration laws,” he said, speaking at a press briefing.

The funding threats to sanctuary cities are not entirely new. Last year, the Obama administration said cities which failed to comply with federal immigration law put themselves at risk of losing funding.

But local law enforcement in cities around the nation say that refusing to hold nonviolent, minor offenders until immigration agents arrive helps to bolster a healthy relationship between police and minority communities, which in turn results in a higher rate of reporting crimes and makes it easier to speak with witnesses who do not have legal documentation.

Dozens of U.S. cities and towns consider themselves sanctuary cities.

[In Santa Fe, New Mexico, the city council voted to become a sanctuary city in February after advocacy from local churches such as United Church of Santa Fe. Allegra Love, an immigration attorney who attends the church, told United Church News: “Sanctuary does not keep ICE out of a city, and we need to all be ready to protect our neighbors from raids and arrests.”]

A version of this article, which was edited on April 7, appears in the April 26 print edition under the title “Sanctuary churches, cities may face consequences from federal authorities.”