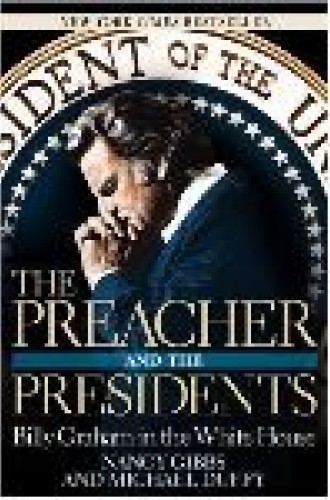

Pastor to presidents

In this captivating narrative, Nancy Gibbs and Michael Duffy, veteran reporters for Time magazine, offer details of Billy Graham’s historic relationships with every U.S. president from Harry S. Truman to George W. Bush. Many of the details are reported here for the first time, and they are at once comforting and troubling, predictable and surprising, funny and tragic—everything we would expect from personalities as big as Graham’s and, say, Bill Clinton’s.

Graham has not granted interviews to all those who have sought access to him in recent years, but Gibbs and Duffy were able to visit with him four times at his rustic home in Montreat, North Carolina. The content of these interviews, including others with several past presidents and key presidential aides, makes The Preacher and the Presidents one of the most significant contributions to the study of religion and politics in the United States in the 21st century.

Gibbs and Duffy are sympathetic to the immensely likable Graham, and when reading their book, I could not help recalling Tom Wicker’s barbed comment that William Martin had taken a “reverent approach” in his 1991 biography of the evangelist. Gibbs and Duffy are not so much reverential as deferential, but the effect is the same: Graham largely escapes the scathing critique he occasionally deserves.

It’s not that the book lacks criticism. Gibbs and Duffy give the bulk of their attention to Graham’s relationship with Richard Nixon, and here they find more than a few things that raise their eyebrows, including Graham’s “fascination with power,” his uncritical patriotism in the face of massive political dissent, his focus on Nixon’s political rather than spiritual needs and, yes, his damning comments about Jews in the infamous Oval Office meeting in January 1972.

Perhaps most disappointing is the way Gibbs and Duffy treat Graham with kid gloves when recounting his stance on the Vietnam War. The authors claim that it was “fair” of Graham to tell the New York Times in 1973 that he had questioned the wisdom of the war from its beginning. Surely Graham’s July 11, 1965, letter to Lyndon Johnson, for some reason not cited by Gibbs and Duffy, is evidence enough to counter Graham’s revision of history. Graham wrote: “The Communists are moving fast toward the goal of world revolution. Perhaps God brought you to the kingdom for such an hour as this—to stop them. In doing so, you could be the man who helped save Christian civilization.”

The post-Nixon sections of the book are by far the most compelling and groundbreaking. Especially fascinating is the account of Graham’s transformation in the painful aftermath of Watergate.

The authors report that shortly before Gerald Ford took office, Graham arranged for a private meeting with Billy Zeoli, Ford’s pastoral counselor, and offered a lesson he had learned the hard way: “When you get to the White House, don’t play golf with him,” Graham stated. “Don’t go on the Sequoia with him. Don’t make it a social event. Be yourself. You have to ground him in scripture.” (And this from a man who swam naked in the White House pool.)

Gibbs and Duffy make much of this change, even suggesting that it helped to save Graham’s public image and ministry. But Graham did not always follow his own advice in the post-Nixon years—the vacations he took with the Bush family in Kennebunkport come to mind. Perhaps what really saved Graham is that no succeeding president was quite like Nixon.

Nevertheless, Gibbs and Duffy do convincingly show that after the scorching of Watergate, Graham focused more on his role as pastor to the presidents. At no time was this more evident than during the Lewinsky scandal, when Graham publicly announced that he had forgiven Bill Clinton, a move that infuriated many conservative Christians. Offering the type of rich detail that makes this book a treasure to read, Gibbs and Duffy relate a touching story about Graham and Clinton at an event shortly after the scandal broke. The organizers of the dinner marking Time magazine’s 75th anniversary did not plan for Graham and Clinton to sit together, but when baseball great Joe DiMaggio refused to sit next to the president, Graham volunteered to take his place. According to Gibbs and Duffy, “This was trademark Graham: the more trouble a president was in—Johnson over Vietnam, Nixon over Watergate, Clinton over Monica—the more prepared Graham was to stand publicly by his side.”

The authors leave out an inconvenient exception: Jimmy Carter during the Iran hostage crisis. Although they were fellow Southern Baptists, Graham and Carter never became close friends, and this emboldened Graham to act in ways that were contrary to his earlier deference to sitting presidents. Rather than standing by Carter during the crisis, Graham called a private meeting of conservative religious leaders to plot their backing of the future darling of evangelical Christianity—Ronald Reagan. Perhaps this move points to the true hallmark of Graham’s political ministry: no matter a president’s (or presidential candidate’s) political or religious affiliation, the greater a friend he was to Graham, the more prepared Graham was to stand by his side, in public and in private.

Friendship, of course, did not keep Graham and the presidents from using each other for their own purposes. Graham was fully aware that presidential connections could give him access to areas often closed to missionaries (for example, India, South Africa and Russia), and presidents were delighted that Graham could give them an entrée into the vast bloc of evangelical voters and could grant religious legitimacy to their candidacies, policies and wars. This mutual usefulness tended to encourage both Graham and the presidents to keep their mouths shut in moments of disagreement.

Graham might have been at his best when he privately comforted troubled presidents, sharing thoughts about the afterlife with Dwight Eisenhower, talking about the second coming with John Kennedy or encouraging George W. Bush to get right with God. But when he lobbied for Johnson’s War on Poverty, encouraged Ford’s pardon of Nixon, praised Carter’s embrace of the SALT treaty, lobbied senators to support Reagan’s decision to sell AWACS to Saudi Arabia, stayed with George and Barbara Bush at the White House on the eve of the Gulf War, carried messages to North Korea on behalf of Bill Clinton and offered a virtual endorsement of George W. Bush in Florida just days before the 2000 presidential election, Graham was acting as a political broker extraordinaire, who, with eyes wide open, placed his celebrity status as America’s preeminent Protestant in the service of presidents he dearly loved.

Better than anyone else to date, Gibbs and Duffy describe and document what we have long suspected: that in spite of his many pronouncements that he was staying out of politics, Billy Graham was far more than just a preacher—before and after Watergate. That they do not tell the whole story of Graham’s relationships with U.S. presidents is no fault of theirs. The story is incomplete because Billy Graham, for reasons unknown, has refused access to his personal papers. Until these papers become public, we can only imagine the full story of America’s most political preacher.

Michael G. Long is author of Billy Graham and the Beloved Community and editor of The Legacy of Billy Graham: Critical Reflections on America's Greatest Evangelist, forthcoming from Westminster John Knox.