The abortion lady

Writer-director Mike Leigh’s Vera Drake is about a real-life figure jailed in England in 1950 for administering abortions. The film’s point of view is pro-choice. Its thesis is that two evils—the illegality of abortion and the repressiveness of British domestic life in the mid-20th century—made it necessary for someone like Vera (Imelda Staunton) to help working-class and middle-class women who were “in trouble.” The phrase alludes not only to the plight of pregnant unmarried girls but also to that of wives whose sexual duty to their husbands stranded them with families so large that the work of caring for them was backbreaking and the means of feeding them insufficient.

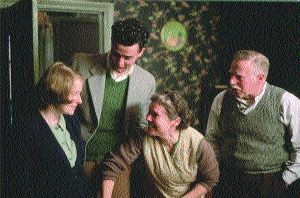

Whichever way one leans on the topic of abortion, it’s easy to see how Leigh has rigged the argument. Vera is portrayed as a woman of infinite compassion for whom these clandestine treatments are an extension of the kindness she doles out to family and friends in the course of her day. When she isn’t at work (she cleans houses) or caring for her own family—a devoted husband, Stan (Phil Davis), a grown but as yet unmarried son, Sid (Daniel Mays), and a daughter, Ethel (Alex Kelly)—she’s in and out of her aging mother’s flat or lending a hand with ailing neighbors or cooking for Reg (Eddie Marsan), a lonely bachelor who winds up engaged to Ethel.

The fact that the film doesn’t distinguish between these activities, which Vera discharges with unfailing cheeriness and sensitivity, normalizes the abortion business; the women’s troubles are an unavoidable by-product of life in this society. She responds to them in secret because, in the movie’s clear view, the holdover Victorian mores oppress women and demonize the only means they have for relieving their dire situations.

Vera doesn’t accept money for what she does; she’s shocked that the cops who arrest her would suggest such a thing, and appalled to learn that a friend who puts many pregnant women in touch with her is taking a commission for the work. Vera’s treatments are safe: she uses a syringe and a mixture of carbolic soap and water. A woman who’s hospitalized, and whose doctor alerts the police, is the only one in 20 years to come to any harm. Vera’s mother (Lesley Sharp) is reluctant, even hostile, when the cops press her for the information that leads to Vera’s arrest. No woman in the movie is on the side of the law. Not even all the men are. Reg, who grew up with five siblings living in two rooms, delivers a heartfelt defense of Vera’s work.

Leigh’s other technique is to contrast Vera’s story with a plot about a rich girl (Sally Hawkins) who is sent by a friend to a high-priced doctor for an abortion. The doctor agrees to perform the abortion after a psychiatrist declares that she’s so depressed her health depends on it. Leigh is just as sympathetic to this woman as he is to Vera’s patients. She’s a rape victim terrified to reveal her condition to her chilly socialite mother (Lesley Manville). It’s clear that Leigh isn’t out to skewer the needy women of any class.

Leigh is a terrific filmmaker. His visual portrait of the period, aided by Dick Pope’s marvelous cinematography, is so evocative it’s almost uncanny. And the ensemble acting is superb—a trademark of Leigh’s movies. In the first half, the filmmaker uses the courtship of Ethel and Reg, a comically odd couple straight out of Dickens, to vary the tone. But the rigid way the drama is calibrated to put across the argument dooms the second half to melodrama.

In jail, Vera the working-class saint is reduced to weepy shame—not for her conduct, but for the humiliation she’s brought down on her respectable family. At that point, not even an actress of Imelda Staunton’s impressive resources can devise anything interesting to do.

The second hour of Vera Drake is a dreary soap opera with no real dramatic action, just a predictable playing out of Leigh’s thesis. Vera’s upper-class employers refuse to appear as character witnesses in her behalf or link themselves to her scandal. The judge who sentences Vera (Jim Broadbent) isn’t concerned with her character or with the fact that she’s received no financial benefits from her illegal activities. He gives her the stiffest sentence the law permits. The final image is of Vera shuffling to her cell, weighed down by adversity, a martyr at the hands of an unreasonable society.