Oscar Romero's grain of wheat

This month in 1980, the Salvadoran archbishop was assassinated—shortly after preaching on John 12.

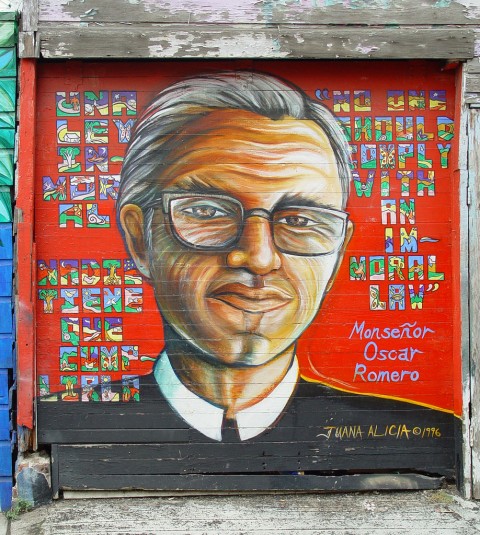

When I was growing up in D.C. in the 1980s, many of my neighbors were Salvadorans who had fled the violence of civil war. My parents and many of their colleagues were active in opposing U.S.-funded suppression of leftists in that war and others in Central America. All of them held up Archbishop Oscar Romero as an example of highest virtue (never mind the Vatican delaying his cause for sainthood until recently). And since the March 24 anniversary of Romero's assassination usually falls during Lent—next Tuesday will be 35 years—the church in which I was raised remembered his martyrdom as we pondered the sacrifices that come with discipleship.

During a trip to El Salvador a decade ago, the delegation I was part of visited the hospital grounds in San Salvador where Romero lived. I can still picture his sparse bedroom and the chapel where he was killed—shortly after preaching on John 12:23-26, part of this Sunday's lectionary Gospel reading.

The day before his death, Romero publicly pleaded with his nation's soldiers to disobey unjust orders and stop the repression. He called on them to listen to the voice of God, whatever the cost.

Romero had done this himself. Up until 1977, three years before his death, he was seen as a “quiet, pious, conservative cleric,” according to Catholic peace activist John Dear: “Indeed, as bishop, he sided with the greedy landlords, important power brokers, and violent death squads.” Most social-justice-loving priests and scholars in El Salvador judged Romero as someone who couldn’t be an ally.

One who saw his potential was Rutilio Grande, a priest who was working to help the poor remember their own dignity and worth. When agents of the Salvadoran government gunned Grande down, Romero heard God's voice telling him to speak out. "When I looked at Rutilio lying there dead," he said, "I thought, 'If they have killed him for doing what he did, then I too have to walk the same path.'" Some call this Romero's conversion. He saw it "as a development of the same desire I have always had to be faithful to what God asks of me.”

This week's epistle reading says that Jesus "learned obedience through what he suffered." Romero did this as well. Knowing that his friend was killed for his ministry empowering the poor, Romero could have become more fearful, more anxious to preserve his life. Instead he chose to let God continue to shape him into the person God wanted him to be.

When Jesus speaks of those who “hate their life in this world,” the word, miseo, could also be translated “to think of as less than” or “to have relatively little regard for.” Biographers paint a picture of Romero as a man who wanted to continue to live and to serve his people. But he didn’t regard his life as being worth more than those of the many poor farmers—along with priests, nuns, and lay leaders—who were being murdered by death squads.

“One must not love oneself so much as to avoid getting involved in the risks of life that history demands of us,” Romero said in that final homily [pdf]. “Those who try to fend off the danger will lose their lives. Those who out of love for Christ give themselves to the service of others will live like the grain of wheat.”

With that grain of wheat, as with Jesus, the emphasis is not on dying but living. Die has always struck me as an odd word choice in this passage from John. At first I thought it could be a translation issue, with the different shades of meaning we preachers love to dig into, but my Greek New Testament and lexicon said otherwise. In John’s Gospel, both a grain of wheat and Jesus “cease to have vital functions”; they “decay” when placed in the ground.

That makes me think that this image is pointing us toward how Jesus’ death is different from other deaths. I’ve placed a lot of seeds in the ground, and I've nurtured the sprouts as they become plants and bear fruit. I’ve watched seeds bring forth life—not ceasing to have vital functions, but pushing off the old in order to allow the new to emerge and mature.

Bearing fruit in our lives might not require us to die a martyr’s death. But we do have to be willing, like Romero and like Jesus, to listen to the voice of God whatever the cost.