God's love, our bodies

Turned toward one another in worship, we experience the grace of God's gaze.

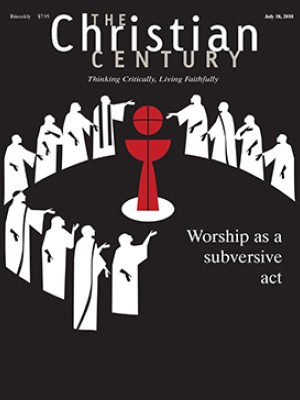

I arrive early to set up for worship. I work in the dark, the sanctuary like a womb ready to birth us into the world, to form us into a body—into Christ’s life. The Presbyterian church from which we rent worship space assembles its chairs in rows facing the stage, directing the gaze of the congregants toward the altar and pulpit. Each week we move the chairs to form a semicircle. We prefer to look at each other during worship. Each person is a holy altar; every mouth proclaims God’s word. Our eyes flicker with the Spirit’s life.

“What is this place where we are meeting?” begins the hymn by Huub Oosterhuis, the first entry in our hymnal. “Only a house, the earth its floor.” I hum this song as I push chairs into new rows. “Yet it becomes a body that lives when we are gathered here.” The place is sacred because God has consecrated us as living signs of divine presence. In the last verse of the hymn, the worshipers become the sacrament of Christ’s body: “Here in this world, dying and living, we are each other’s bread and wine.”

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The hymn resounds with Catherine of Siena’s theology of “the food of souls”—a spirituality in which, as she wrote in the 14th century, “our souls must always be eating and savoring the souls of our brothers and sisters. In no other food ought we ever to find pleasure.” Catherine uses the Italian word dilettare to describe our holy enjoyment, a word that means “pleasure” or “delight.” We delight in God’s sustaining grace in the pleasures of our fellowship, in our communion of souls. As the medieval historian Ann W. Astell explains, “Catherine stresses the reciprocal relationship, the Communion between those who eat and those who are eaten, their mutual neediness, and the permeability of the ‘I’ who lives for and by others.”

To turn our chairs is to beckon our bodies to reveal the neediness hidden in our souls, the permeability at our core—that “we live for and by others.” We are beggars, gathered to receive grace. We are priests, consecrated to administer the sacraments with our hands as we pass Christ’s peace, with our songs as we breathe the Holy Spirit, with our eyes as our gaze welcomes each other into God’s beauty. “Whoever sees the church,” says Gregory of Nyssa, “looks directly at Christ”; our gathering reveals “the beauty of Christ’s body.”

This gaze reveals the boundaries of the body—not only the church as the body of Christ but also each of our physical lives, the skin that distinguishes you from me. I cannot see my whole body, I cannot know myself by myself. I’m too close to me to know who I am, to know the curves of my being. You show me who I am, as I see reflected in your eyes the shape of my body, the contours of my self. Our relationship reveals my identity—I am found in your gaze. We bless each other with the words Jacob says to Esau: “To see you is like seeing the face of God.”

Not all gazes are the same. Not all eyes look with love, and not all desires honor another’s dignity and beauty. Some stares flatten others into commodities, into objects whose value is determined by usefulness, bodies without agency or depth of consciousness. That type of look turns people into property, refusing to recognize others as having their own boundaries. Those eyes prefer coercion to consent.

Several years ago a member of our church told me that he learned the graces of a gaze, the mutuality of a glance, at our worship service. He learned how to receive another’s attention without looking away in fear, in embarrassment at the thought of exposing his human neediness for connection. Turned toward one another as we worshiped, he beheld God’s affirmation of his life as he rested his self into the sacrament of our reciprocal gaze, the grace of Christ’s body receiving him as a gift, the divine presence refracted in him for us. To be held by a gaze—that’s how we draw each other into God’s loveliness.

“Whatever you bind on earth will be bound in heaven,” Jesus tells his disciples, “and whatever you loose on earth will be loosed in heaven.” I want our congregation to be known as people who loose God’s love into the world, who worship as the Holy Spirit binds heaven and earth together in us, our body revelations of incarnate wonders. We invite others into God’s gaze, holding us with gentle care and tender affirmation of our lives. Each glance across the sanctuary glimmers with divine affirmation, eyes welling up with affection, glimpses into the depths of God’s love for the world.

Our worship space becomes “a body that lives,” we sing in Oosterhuis’s hymn, “when we are gathered here, and know our God is near.” As we turn our chairs, the Spirit is as close as the gaze reaching between us, eyes gleaming with our soul’s delight. Our fellowship materializes joy, the ecstatic leap of God’s triune love into our corporeal selves.

“Come, abide within me,” we declare in another of our gathering songs, “let my soul, like Mary, be thine earthly sanctuary.” Our bodies together in rented space become Marian as we bear God within us, forming an earthen sanctum for the Spirit.

After worship, after the laughing and talking in the fellowship hall, after the last parents load their children into car seats, I linger in the silence and rearrange the chairs, returning them to their rows.

I imagine the mess as the remnants of a holy birth: the people as Christ’s body delivered into the world, good news born again this week. They are the gospel alive, loosed into schools and workplaces, neighborhoods and communities. They are incarnations of grace.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “Holy gaze.”