Displaced Iraqi Christians await return to Mosul

Two years ago, when fighters from the self-described Islamic State began their assault on Karemlash, a town 18 miles southeast of Mosul, Martin Banni, a Chaldean Catholic priest, grabbed communion elements, the church’s official documents, and a few personal items and fled.

More than 100,000 Christians from the area had already left. The archbishop of Mosul begged Christians to flee.

“We were few in number with no weapons, and we could do nothing to face the Islamic State,” Banni said. “We ran.”

As Iraqi forces began an offensive to retake Mosul, pushing the IS out of neighboring towns in late October, Iraqi Christians on the Nineveh plains hoped their time in exile would soon end.

“I stay awake all night following the news,” said Abu Adrian, a teacher in Alqosh, a mountainous Catholic town 31 miles north of Mosul that escaped IS control. Adrian hopes that soon it will be possible for “our people to return to their hometowns and homes after this long struggle.”

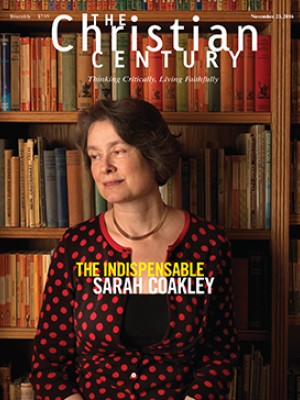

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Since 2014, Alqosh has hosted 600 Christian families who fled the persecution farther south.

There and elsewhere in northern Iraq, the situation for the Christians has become dire. They lack jobs and money, with entire families sharing a tent or a single room. Most fled with only identity papers and the clothes on their back.

“We did not think it would be a no-return departure,” said Banni, who has been displaced in Irbil in Iraqi Kurdistan since 2014. “We thought it would take a day or two.”

Some of these Christians say they had all but given up hope of ever being able to return.

“There was a sense of frustration among people who wondered about the feasibility of staying like this for two years or more,” Banni said. “Besides, they wondered about the time it would take to reconstruct their cities after liberation, if all this time has passed and they still had not been liberated.”

That frustration grew as Iraqi government forces liberated Fallujah and Ramadi over the past 18 months while Mosul and its surrounding towns remained under IS control.

[The United Nations is gearing up to provide humanitarian relief, anticipating that up to 1 million people may be forced from their homes as a result of the military operations in Mosul. William Spindler of the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees said, “There are real fears that the offensive to retake Mosul could produce a humanitarian catastrophe resulting in one of the largest man-made displacement crises in recent years.” He noted that 3.3 million Iraqis—10 percent of the population—are already displaced. Lutheran World Relief and other members of the ecumenical group ACT Alliance are also among the organizations offering aid, including in the Debaga camp, southeast of Mosul, to which tens of thousands of people have fled.]

It is unclear when Mosul exiles would be able to return.

“I have no plans,” said Samer Elias, a 42-year-old Christian Iraqi writer from Mosul who has been living in the Kurdish city of Dohuk. “The future for us Christians seems quite gloomy and obscure.”

And it is uncertain what returning Christians will find. Many, like Elias, don’t know if their homes remain.

[The Dominican Sisters of St. Catherine of Siena, living in Irbil, wrote in a public letter on November 1 that they feared Christian lands would become disputed.

“The urgent question that people are currently asking is: To whom will we, as people and land, belong?” they wrote. “We do not want our heritage to be wiped up when the process of cleaning the land happens.”]

Banni said some of his flock are worn down from the past two years and pessimistic about the future. Some have been considering going to Europe or elsewhere rather than returning home.

But the 25-year-old priest, who was ordained in September in Irbil instead of in his beloved Mosul, already has priorities for rebuilding hospitals and schools.

“This is most important because it ensures our people can come back to their homeland and live in peace there once again,” he said. “The liberation of the region is finally happening and the prospect of going home feels closer now than ever before.”

In spite of how his community has been treated, he hopes the future will be different.

“We want to face our problems and solve them, not to escape from them,” he said. “A people who have borne all these difficulties can never be broken.”

Emad Sabeeh Georges, 36, a sales manager now in Irbil, wants to return to his native Qaraqosh, which was recaptured by the Iraqi army, Reuters reported.

“This is my homeland, the land of my ancestors,” he said. “We have not conquered or taken it by force—we are Iraq’s real sons, and we have learned how to live in peace with others. I insist on going back, to stay, to rebuild, and to change the extremist thoughts around us.” —Religion News Service

This article was edited on November 2.