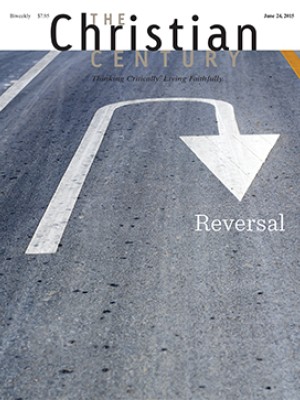

Reversal: Essays by readers

In response to our request for essays on appetite, we received many compelling reflections. Below is a selection. The next topics for reader submissions are lies and road—read more.

I walked to the front steps of a small bungalow, where a middle-aged black woman met me. I told her I was the chaplain from hospice, and she expressed gratitude for my coming. She told me her mother had a bad night and wasn’t very responsive. She took me down the hall to where her mother lay in a hospital bed, photos of her children hanging on the wall.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

I introduced myself, asked a few questions, and offered a prayer. I could see that this tiny, frail woman was nearing the end of her journey. She hardly had enough energy for our brief conversation. I asked a final question: “Do you have a favorite hymn?” There was a long pause. I thought she was asleep or just not answering.

Then, with her eyes still closed, she began to sing, “Pass me not, O gentle Savior, hear my humble cry; while on others thou art calling, do not pass me by. Savior, Savior, hear my humble cry; while on others thou art calling, do not pass me by.” Her voice was frail, but the melody was clear and true.

About a week later I pulled into the driveway, and before I was out of the car the daughter came to the door in tears. She said, “Pastor, pastor, I’m so glad you are here. Momma’s taken a turn for the worse. She isn’t doing well. I was hoping you would come.”

This time there was no response from the woman. Her breathing was labored, and her eyes were closed. The daughter was tearful and left the room. I said a few words, said a prayer, then began to sing, “Amazing Grace, how sweet the sound . . .”

Later I got word that she died that night. I called to check on the daughter. When she answered I could hear excitement in her voice. She told me she was fine and having some quiet time alone, but that she was really glad to hear from me because she had something she needed to share.

“When I was a child, my mom used to ask me to sing to her and to sing in church. I never did. I didn’t think I could. All through my growing up, she begged me to sing until finally I said to her, ‘No, Mamma, stop asking me to sing to you. I promise you, I will sing for you before you die, but please don’t ask me again.’”

“I never sang to her. I never remembered my promise until I heard you singing to her. Then I remembered and when you left, I got her hymnbook, and I sang to her. And then she died.”

Judy Worthington

Franktown, Virginia

"Reaching out to ALL God’s people!” The leadership of the church had enthusiastically endorsed the new slogan. I proclaimed it from the pulpit. We exclaimed it in bold print on our flyers.

And then God gave us Joshua. Joshua showed up disheveled and smelling bad. He asked for money before the service and during the passing of the peace. He sidled up to people at fellowship time with stories of hardship. He kept coming back week after week.

“God put him here for a reason,” I told the congregation. “He walks past three or four different churches to get to our church on a regular basis. Why do you think that is?” God, can you clue me in? I prayed. Why is Joshua with us? What are you doing?

Joshua became legendary. Everyone had an opinion about his situation. Some were brave enough to wonder aloud if “reaching out to ALL God’s people” was a good idea. Others felt called to provide.

One Sunday, after telling his week’s story of his hardship and asking for money, he approached members of the mission team and asked for one of the penny banks they were passing out for donations to the Heifer Fund. He wanted to donate to the campaign.

Another Sunday, he came up to me with a bulletin insert in his hand. “This says you need volunteers for the strawberry festival. Can I help, Pastor Sue? Please, Pastor Sue.” He had a habit of always calling me Pastor Sue when asking for something, as if he was reminding me of my role as his pastor.

“Yes, you can volunteer,” I told him, wondering how the planning committee would respond. “We haven’t assigned jobs yet, so we will get back to you on what you will be doing.” God, are you serious?

The committee accepted Joshua’s offer of help with something between hesitant grace and holy obligation. After a frank discussion about hygiene, he showed up showered, in clean clothes, and desperately eager to please.

I entertained the thought that maybe, just maybe, we were making a difference in his life. We were providing for the “least of these” and showing him how to live in the world. Like most Christians, I’m a sucker for redemption stories. I told everyone how he put down his phone and picked up the hymnal during worship.

But a few weeks later, things began to fall apart. He’d gotten a big check, cashed it, and bought stereo equipment instead of paying his rent. A few weeks after that he invited some people to crash at his place. Now four people were crammed into his two-room apartment, and he couldn’t figure out how to get them to leave. His partner, Kelly, had mental health issues, which now flared up.

Kelly was put in a locked-down mental health unit. Joshua had no way to get there during the two-hour visiting window, so he asked me to drive him. It was a short drive, and we were well enough acquainted for me to believe that he was not dangerous. Nonetheless, I let everyone know what I was doing.

“Can I put these clothes for Kelly in the backseat, Pastor Sue?” I nodded. He tossed a bag of what looked and smelled like dirty clothes in the backseat, got into the passenger seat, and put up his window. I arranged the vents so that I would have fresh air to breathe. He thanked me profusely. As we drove, I asked him if he knew what to expect. He didn’t.

“We will go in and you will have to put all of your things in a locker, then they will wave a wand around your body to make sure you don’t have any metal on you or anything that might be like a weapon. We will sit at a table and you can talk to Kelly, but you will not be allowed to touch her. If she gets upset, you will have to leave. Do you understand?”

He was silent for a moment.

“Will you go in with me, Pastor Sue, please? Please will you go with me?” he pleaded like a child.

“Yes, Joshua, I will go in with you.” When will this end, God? I asked silently. We have all given so much.

We stayed at the hospital for about half an hour. The car ride home was pretty quiet. I was thinking about cutting the grass when I got home. Joshua’s fingers kept jabbing at his phone. I made an effort to be present.

“Are you texting?”

“Downloading music.”

I tried to hide my exasperation. Moments before he had asked for money for food. Just go with it. I refocused on the conversation.

“What are you downloading?”

“Alabama. Have you heard of them?”

“Yes. I like the ‘Play Me Some Mountain Music’ song.”

“I like that one. But this here is the best one. Here listen. It’s called ‘Angels Among Us.’ Want to hear it? Can I play it for you, Pastor Sue?” He held his phone near my ear while I drove so that I could hear the song out of the tiny speakers.

Oh, I believe there are angels among us / Sent down to us, from somewhere up above / They come to you and me in our darkest hours / To show us how to live / To teach us how to give / To guide us with the light of love.

I chuckled. OK, God, I think I get it.

“What, Pastor Sue?”

“Nothing, Joshua. No wait. Thank you, Joshua. That is a lovely song.”

“Yeah,” he said. “It’s one of my favorites.”

Sue Washburn

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Whenever I heard the parable of the Good Samaritan in Sunday school I always identified with the Samaritan and thought the task was to show grace to others.

But at 22 I did my best to resist God. After growing up in a faith-filled home, I stayed away from any kind of faith community. In my mind, I was a unique existential postmodern explorer. I sported a long dangly silver earring in my left ear. I had a mullet—or, as they say in Canada, a “shorty longback”—a few too many years past its prime, and my typical attire was a pair of black Red Wing work boots, ripped-up Levi jeans, and a heavy-metal concert T-shirt. During this time in my life, I listened to and thought about a phrase from Ozzy Osbourne’s album No More Tears, “going forward in reverse,” more than I would like to admit as I was driving my 1986 Plymouth Turismo or working the midnight shift driving a tow motor at a grocery store. As with most bildungsroman narratives, my life was filled with embarrassment, confusion, and adversity.

One day I was riding my Kawasaki Ninja 600R just a little too fast and wrecked it. The day was perfectly clear and hot, but I thought it was a wonderful day to take the curves a little too fast. At the time I had a friend who told me that we weren’t really riding unless we scraped our foot pegs on the pavement when we turned.

I flew off my bike and skidded 50 feet. As I lay motionless by a silver guardrail, passersby stopped traffic to help me. I heard sirens, not fully recognizing that those sirens were for me and that I was the reason the road was closed. I couldn’t move; my back was searing with pain, and my left ankle had a 90-degree angle to it. People at the scene extinguished my motorcycle after it went down a ravine and caught on fire.

The EMTs cut off my pants and shirt and started doing tests to see what part of my body needed medical attention. Then they put me on a wooden board and transported me to the hospital. In the ER, I was met by doctors and nurses who treated my broken ankle and cleaned out the abrasions that extended down to my lower back, digging out the pebbles in my neck. The phrase that resonated with me most was the doctor’s: “Your helmet saved your life, Matt.”

As I was stuck to my bed in the middle of the night, I prayed. It was not a prayer that made deals with God or promised never to be bad. It was a cry for help. I confessed I needed help. I no longer identified with the Good Samaritan; I was the guy sprawled out in a ditch who knew the value of being helped by strangers.

Even 20 years after that happened—now with a wife, two daughters, a Ph.D., a great teaching career, and countless lessons learned—life still comes with moments of bewilderment. It took another nine years before I was reunited with a faith community. But that prayer put me on the beginning of the path that I am still on now—and God continues to answer that prayer each day.

Matthew Beery

Macedonia, Ohio

During my last semester of high school, I took a public speaking class in which we were given the assignment to write, memorize, and deliver a persuasive speech. Memorizing wasn’t my forte, but I was a fairly good extemporaneous public speaker. An assignment was an assignment, and being an overachiever, I was determined to shine at it.

As I tossed around topics, I eventually settled on a subject that seemed to fit with my theological beliefs: why women should not be ministers. Growing up, I had never seen a woman standing in the pulpit, or reading scripture from the lectern, or ushering, or even being an acolyte. In the one or two times I saw a woman preaching on television, it seemed extremely strange.

Through conversations with family members I learned that we all thought it was unorthodox to have a female church leader. In those days I thought that if something seemed out of the ordinary and those closest to me objected to it, it must be wrong.

A close friend who was a fundamentalist Christian helped me develop my argument. She was familiar with biblical texts that supported my stance. She reminded me of 1 Timothy 2 and 1 Corinthians 14. I formulated my argument and wrote the text. In what little time I had remaining in that extremely busy semester, I worked on memorizing the speech.

The day of the speech arrived. We were allowed to have someone prompt us if we forgot our lines, so I asked my friend to sit at the front of the class with my script in hand.

Even after working on the speech and with my friend prompting me, I choked. The words wouldn’t come to mind. My mind continuously drew a blank. I got a C for my efforts. It was the only time in high school or college that I received anything lower than a B for a speech.

My public speaking skills continued to develop in the following years. My views on women in the pulpit took longer to change. But over time I sensed that God was calling me to do the very thing I thought was not allowed.

In my process of theological reversal, I studied women in the Bible who were leaders in the early church. I noticed how God employs everyone to spread the message of God’s love and grace. I have to admit that even after receiving the call to ministry, for a while observing a woman in the pulpit still seemed extremely bizarre. Yet God’s call drove me outside my comfortable box.

God knows each of our strengths and may have been calling me throughout my youth to become a pastor. I believe God hoped all along I would answer the call to ministry—even as I tried to deliver a speech on why women shouldn’t be in ministry. If God laughs, God would have been laughing at me on that spring day in 1991 as I muddled through that horrific speech. And I’m sure God was joyously laughing as I was ordained 20 years later.

Michelle L. Torigian

Cincinnati, Ohio

"You don’t have to be anything more than you already are.” That’s a maxim I use often in spiritual direction. Many people come to me thinking that they aren’t holy enough, or good enough, or strong enough. Then God enters into the picture, and through a three-way relationship (the person, the spiritual director, and God) they realize that they are already more than enough; they simply need to be awakened to that fact and embrace all that is present within them.

As a campus minister I had the privilege of accompanying medical students on their journey to becoming doctors. Working at a secular university, I found myself doing things I never thought I would do. I became the unofficial chaplain of the gross anatomy lab, where—especially on the first day—I would make myself available to talk with students (and to catch the ones that passed out!). I asked the students about their experience of dissecting the human body. I designed stress dolls for their exam times and held vigil in the halls during finals.

The students noticed and appreciated the effort, and a few became more interested in exploring the deeper questions of medical ethics, discernment, and how the experience of dissection was cutting into their own psyche.

Many thought they were bad Catholics or not extremely religious. Some would even use the phrase “I’m strictly secular!” But I’d press a bit and ask how they might be changed by the experience, and many found the very essence of much religious experience: gratitude, hope, and peace. They found that they were gifted and sensitive doctors in waiting.

At the end of one semester I hosted a party in the student lounge. The prospect of free pizza and a brief respite before the next exam was welcomed, and many students came over to chat about the semester and how they thought they did on the exam.

C. J. was one of the students I had grown fond of throughout the semester. He often brought his colleagues to mass or campus ministry events. He was deeply introspective but also a lot of fun to be around. He radiated enthusiasm.

“So? How’d you do on the test?” I questioned.

“I did OK, I think. I know I got one whole section wrong, but that should be OK.”

“Does that mean if you got the section on the brain wrong, I should hope you don’t become my neurologist?”

“Exactly! So what are you going to do over winter break?”

I told him that I was thinking about becoming a deacon in the Catholic Church.

C. J. said, “Why do you want to do something like that?”

I was baffled by the question. C. J. was, after all, a strong and faithful Catholic.

“Well,” I said. “I think it would give me the ability to attract more students. I could preach more, do weddings, preside at funerals.”

C. J. said, “I’m going to play devil’s advocate and say that you shouldn’t do it at all!” I asked him to go on.

“Mike, look around. Nearly my entire medical school class is in here right now. Even the atheists! And they’re not here just for free food. People have gotten to know you and to feel comfortable around you, and you’ve been a great companion and mentor to us and made us think about more than just what we learned in class.”

He went on: “You know, I sent out the invitation to our class for this party and put down that Mike Hayes from Campus Ministry was going to throw us a party. If I had put Father Mike Hayes or Deacon Mike Hayes down, there would not only be fewer people here for the party but throughout the semester people might have been scared away.”

And then he said what we all need to hear. “You don’t have to be anything more than you already are!”

I asked, “Who’s the campus minister here, me or you?”

Mike Hayes

Buffalo, New York

"What about hell? What about Satan?” shrieked the retired pastor sitting in the back row of my ordination council. My mentor had warned me that having no mention of damnation in my ordination paper was going to get me into trouble, but I had stubbornly insisted.

“Hell has no power over me,” I replied smugly. A murmur of approval swept the room, and a far too self-assured me was approved for ordination.

So it was that I was ordained with a naive ordination paper. My paper said what I truly believed at the time—that there is no hell. There is no damnation. Everyone would come to accept Jesus, and so everyone would go to heaven some day. I believed that what I called “christocentric universalism” was true.

There have been times over the years that I have wished for that naïveté to return. There have been times I have wished I could look around my community and know with absolute certainty that all the people I meet would eventually give in to God’s call.

One thing I know: I know that God loves more than Christians. I know that God works through the rabbi two blocks from my church, giving her far more scriptural knowledge than I will ever have. I know that God works through the woman from the mosque—who sits on that multifaith panel with me at the university—for she speaks with a compassion I experience only in my dreams. I know God’s saving power, and I see it in people who were not included in my old ordination paper.

Then there’s the other thing that I now know: hell is real. I’ve seen it. I’ve been there. I’ve had those moments, usually self-imposed, when I have completely separated myself from loved ones, from God, and even from myself. I have sunk so far into self-loathing, trying to cover it up with a smile, that I have forgotten more than the gifts God gave me. I have forgotten . . . me! I’ve had those moments of being truly and utterly alone—bereft of my very soul—which is far more terrifying than any fire or brimstone.

I’ve met other people who have also been separated from God and from their true selves. Sometimes we have talked, and they have found their way to a Savior who understands. Sometimes they have chosen to stay in their aloneness. Sometimes they simply cannot climb out of the darkness, no matter how hard they try. We know that hell is real.

Thanks be to God, there is also one other thing that I know—something I remember from back in my creedal, pre-Baptist days: “He descended into hell. On the third day he rose again.” It’s a reminder that while I was wrong and hell is real, it is not to be feared. For the God who saves me beyond my comprehension has already been there, and has overcome it.

Stephanie Salinas

Bangor, Maine

We’d met them only through photos. Two small girls standing, smiling shyly, one looking right at the camera, the other looking up to her sister for assurance, as if to ask, is this OK? Are we going to be OK? They stand there, tiny for their ages, tops entirely too small, skirts entirely too big.

We’re surprised that there are two. Two little girls to join our family. Two more beds, two more bedtimes, two more cups with foam letter names, two sisters for our daughter. We’re thrilled, giddy, and frightened. We’d not imagined being a family of five. Do we need a new car? Do we need a bigger house? I’m not sure, and then suddenly I am confident that this is good. My husband says he is sure. Our daughter yelps and jumps up and down when we tell her. “I’m getting sisters!”

We receive no news for a very long time. When we seek information, there is no written report, no verbal update. We look again at the photo. Gorgeous smiles, beautiful girls, so small, so fragile. We are ready to love them in person instead of from far off.

Then there is a phone call from our adoption agency. The woman on the line says she has news that may be hard to hear. The birth family has come forward, she bursts out. This family did not know what adoption was. They did not understand that it’s forever and that the girls would not be coming back to them. She has to retract the referral of the two girls.

I am not surprised. I am calm, actually. We half expected it, I say. Things didn’t look right on paper. We are sad for us, we are glad for them I say, meaning it. I hang up the phone and then I am quiet a long time. I pick up the phone and dial my husband at work, then hang up. He should be able to get through the day without bad news. But I remember our promise to each other: we share all these things. I pick up the phone again and dial.

He picks up on the second ring. I tell him, not asking if he has a minute. He sighs. He is quiet and then says, “We always knew this was possible. I don’t like it. How will we tell the kid?”

“I don’t know, I don’t know. Let’s get to the weekend.”

“OK,” he says.

I sit some more. Eventually I get up, eat lunch, pay bills, and run errands. This is not how I’d imagined my day off. I call a friend. She says she is sorry in her northern Minnesota accent. She says she will be in touch.

And she is. She comes over that weekend. Maybe it’s too soon, she says. Maybe you cannot let them go. We have to, I say. We’ve told our daughter.

Our friend has brought a bag full of paper, crayons, and art supplies. She asks us to make a drawing or write a poem about how we will miss them. Are there actually words for this?

Our daughter makes her creation: a drawing of the five of us, smiling. She puts a large X through it. Next to it she puts a drawing of the three of us with deep frowns and tears.

Let’s send these writings and drawings up to heaven as a prayer, our friend invites us. We say OK. We move silently outside, where it is drizzling. We go back in for matches. We move the fire pit closer to us on the sidewalk. We put the drawings and poems in the pit. We strike the match. We watch as those dreams, prayers, hopes, and worries get turned into a wisp of smoke, a continual prayer for those two girls. A prayer for us as we move forward, wondering about them, wondering about us. It begins to rain harder. We go back inside.

Several days later our daughter stops suddenly and points up. “I still see it. Do you, Mom?” I look up. “See what, dear?”

“The twist of smoke, our prayers,” she continues. “God hears us, and the girls hear us too. I hope they remember us, how much we loved them. Mom, I never knew you could love something you haven’t touched.”

I finally inhale. “Me neither sweetie, me neither.”

Amy Wiegert

Chicago, Illinois

For three years in the 1970s I was the senior Protestant chaplain at an air force base in the Midwest. One day Sgt. Bill Sochko came to my office. I had never met him. He said he was raised in the church but had long since fallen away. Now he wanted to reconnect. “How do I do that?” he asked. “We worship at 1000 hours every Sunday, Bill,” I responded. “Come and join us.”

The next Sunday Bill was there. Soon I noticed that he was serving as an usher. Then he showed up at our weekly Bible study. For as long as my assignment lasted, Bill was totally involved in our chapel program.

Soon after I was reassigned, the base closed. All personnel were ordered to other bases. I didn’t know what became of the base.

Years later I had occasion to travel close to the old base and decided to check it out. To my surprise, all the buildings were intact, but they appeared to be abandoned. The gate was open—no security guards, no ID checks. I drove down the main drag toward the chapel. It was eerie, to say the least; no troops, no vehicles, just an empty, surreal silence.

When I noticed a car parked at the chapel, I decided to stop there on the chance that I might find an unlocked door. I did. Traversing the empty halls, I came to my old office. It was full of storage boxes. I poked my head in the sanctuary. Surprisingly, it looked just like it had decades earlier, except for a set of drums in the chancel. So maybe something was still happening there.

On my way out I noticed that the main office door was slightly ajar. Looking closer I saw an old man with a full, gray beard holding what appeared to be a Bible. Now I was really curious. I knocked on the door, and the elderly gent bid me to enter. In the room I saw two young people and concluded that he was conducting some sort of Bible study.

Not wanting to be too intrusive, I asked, “What happened to this base?” He said that after it was closed the state took it over and converted a portion of it to a correctional facility for youthful offenders.

“What about the drums in the sanctuary?” I asked.

“I got permission to run a religious program for the inmates. We worship there every week.”

“There must be some expense associated with this activity,” I conjectured. “Who funds it?”

“I do,” he said with just a hint of pride.

“This is amazing,” was all I could say.

Then, turning to leave, I said, “I’m Chaplain Valen. I served here many years ago.”

“I know who you are,” he said with a broad smile. “I’m Bill Sochko.”

David Valen

Plymouth, Minnesota