Scene at the table: A disruption on Maundy Thursday

As I came to the first student and his family, kneeling with outstretched hands, suddenly someone took out a phone and snapped a picture.

Last year, my church made Maundy Thursday the day for the fifth graders’ first communion. While this practice is a long tradition in some places, for us it was new. We hoped to connect the children’s learning with the experience of Holy Week. Also, for the past several years Maundy Thursday attendance has skewed older, so we hoped to generate some intergenerational interest in the first of our three Holy Week services.

There were just five fifth graders last year, four boys and one girl. In preparing for first communion, we had fun experiences and good intimate conversations. Then came Maundy Thursday, that somber evening service culminating in the chanting of Psalm 22 and the stripping of the altar. Before the service started, the students and their extended families gathered, along with those who faithfully attend every Holy Week event. One couple was recently divorced, and each brought a new partner. There were a few introductions and some awkward shyness.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

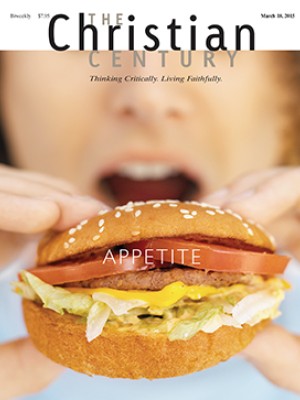

I had prepared a short and simple sermon, all about eating and welcoming and how we remember Jesus. I remember looking out into the congregation that night. It seemed even smaller than usual, despite the fifth graders’ families. They were the first to come up and kneel around the altar to receive communion, a posture that isn’t our norm but seemed right for Maundy Thursday.

As I came to the first student and his family, kneeling with outstretched hands, suddenly someone took out a phone and snapped a picture.

A little conversation took place in my head. On the one hand, I longed to be inclusive and welcoming. If we are really serious about being a place where seekers are welcome—where people can bring their real lives before God—we will need to get used to this kind of thing and not judge it.

On the other hand, I remembered a pastoral mentor’s strict policy on cameras in church. She told me once that if someone tried to take a picture during a wedding, she would reach out and take the camera away. This is worship, after all! I could not imagine myself doing the same thing, but I was sure this reflected a lack of leadership on my part.

It was an incongruous scene: the camera, the altar, the holy night. I had a hard time reconciling it. It didn’t seem holy to take a picture; it made me uncomfortable. But when I asked myself why, my answers didn’t seem that compelling. I was also very aware of the fact that the choir was sitting directly behind me. I was ready for indignant comments from the congregation, though these never came.

Later, I noticed that the photo in question was posted on Facebook. This was unremarkable in itself. It was the caption that struck me, the description of those pictured. In the photo was one of the fifth graders, kneeling between his estranged parents. Both are smiling at their son. Despite their differences, they had come together that night for the sake of their beloved child.

The photographer was engaged to one of the parents. I don’t know why she snapped the picture. Perhaps in a moment when everything seemed awkward, it was simply something concrete she could do. But what I imagine is that she saw something I did not see, noticed something I was not paying attention to. Somehow she saw the table of reconciliation, the promise of the one who feeds us at the table. She caught a glimpse of the new commandment, the commandment to love one another as Jesus loves us.

We are reminded again and again how difficult this is. Every time Jesus breaks the bread, every time we break a promise, every time we break a heart, we are reminded of the impossibility of this commandment. But every time we break the bread, we are also reminded of the one who brings us together for the sake of his beloved child.

Looking back, I am not sure what made me so uncomfortable in that moment. Was it was the idea of the modern age breaking in on the ancient story? Here we are again, reciting the 2,000-year-old story of the upper room, remembering how Jesus broke the bread, washed the feet, went to the cross. Here we are in this old-fashioned sanctuary shaped like an ark, and the phone with the camera seems so out of place—reminding me that it really isn’t 2,000 years ago, that it is the 21st century, in which so much is different.

Or maybe it was just the chaos of the thing, the unplanned disruption in the midst of a sacrament. I like things to be well rehearsed, to flow smoothly, and this was interrupted by an unscripted moment. Perhaps there is a part of me that would like to leave Jesus’ story of reconciliation in the past, where I have illusions that I can control it.

Yet I can still see the picture in my mind: the child in the middle, his hand outstretched. His parents are smiling; they have laid aside their weapons. They will take the bread and the cup. And in the midst of that ancient story, in the chaos of life right now, someone took a picture. Someone photographed “love one another, as I have loved you” so we would all know what it looks like, and how hard it is.