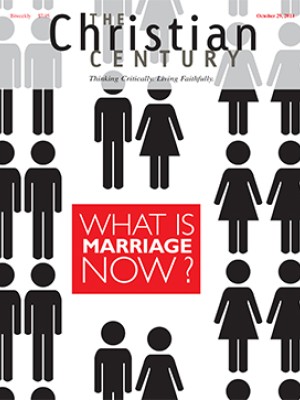

What is marriage now? A Pauline case for same-sex marriage

Amid endless debates concerning same-sex relationships and same-sex marriage, one biblical passage is often curiously absent. In 1 Corinthians 7, Paul reflects on the merits of married and single life. If unmarried persons struggle with sexual self-control, he says, they should marry, “for it is better to marry than to be aflame with passion.”

The King James Version translates Paul’s sentiment more bluntly: “It is better to marry than to burn.”

Wide embarrassment on all sides no doubt accounts for neglect of this passage—but also makes it an unexpected resource. If no side owns it, the passage may offer a rare place to meet for fresh discernment. If no one likes the passage, its very neglect might offer an unexpected way out of our impasse.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

That impasse is one I have lived. As a Catholic moral theologian I’ve struggled for more than two decades with the pain of those with same-sex attractions and relationships who face rejection from families and churches that claim to offer the deepest love. To experience such a gap is to sense a betrayal—a pain that, by cutting into one’s very identity, may wound more than do bullying and violence.

Yet the pain of others is quite real too. Unjustly dismissed as homophobic, some are simply reeling from the sexualization of culture and the corrosion of stable family relationships. They may unfairly grab on to homosexuality as the ultimate sign of a breaching of those cultural assumptions and of a natural order upon which they’ve built their lives. But they have legitimate concerns and valid questions.

I also write as the husband of a Mennonite pastor of a welcoming congregation who is prepared to officiate same-sex weddings. My wife and I have taken our churches’ pain, struggles, and arguments deep into our marriage over the years. Because she’s a pastor who is sensitive to local needs, she focuses on different points than I do as an ethicist seeking to reconcile an array of positions and concerns.

However improbably, I have found Paul’s approach in 1 Corinthians 7 offers a path out of our impasse and toward broader churchwide consensus concerning marriage. Extending the blessings of marriage to same-sex couples by recognizing their lifelong unions fully as marriage could allow the church to speak all the more clearly to what deeply and rightly concerns those who seek to uphold the sanctity of marriage. But the opportunity opened here is also a responsibility—to renew Christian teaching concerning why God’s intention is that full sexual intimacy belong solely to marriage.

In a rare remark within his letters, Paul takes pains to clarify that his counsel in 1 Corinthians 7 may carry no special authority from the Lord and may only reflect the wisdom he has gathered from personal and pastoral experience. A turn to personal experience is striking coming from Paul, an apostle who’s had a direct revelatory encounter with the risen Lord. Yet here he’s ready both to draw upon the complexities of messy human experience and to forthrightly recommend a compromise or concession.

Heterosexual marriage was actually that compromise. Instead of the indispensable biblical value that some contemporary churches project marriage to be, marriage was a practical solution for Paul and apparently a “second best.” Far more urgent were the kingdom values and tasks that pressed upon the community in light of Jesus’ expected return. At least in 1 Corinthians, the main purpose of marriage was not even the protection and care of children or the benefit that accrues to society through such care. Marriage was the better choice for Christians if and when they needed to deal with otherwise uncontrolled sexual desire.

No wonder the Pauline remark is hardly a go-to text in current debates over same-sex marriage: impassioned advocates as well as fierce resisters find it embarrassing. Churches that once held the vocation of celibate religious life to be above married life (and only reluctantly called marriage a vocation) now celebrate both ways of life as callings equal in status. So-called conservatives and so-called liberals agree on this much: both are glad that today’s church has a more exalted view of marriage than Paul did.

In the fifth century of Christianity, Augustine defined three chief “goods of marriage”: permanence, faithfulness, and fruitfulness (sacramenti, fidei, prolis). When ancient church leaders associated faithfulness mainly with the Pauline solution for lust, they were citing only one of three goods or purposes. Likewise, Christian interpreters today may continue to see procreation and child rearing as the prototypical expression of fruitfulness, but not as the only one. Every Christian marriage should face outward in hospitality and service to others.

Together with permanence, therefore, faithfulness has come to stand for all the ways that couples bind their lives together. Spouses do not practice faithfulness only by giving their bodies exclusively to one another in sexual intimacy, but by together changing dirty diapers and washing dirty dishes, by promising long and tiring care amid illness and aging, by offering small favors on very ordinary days.

In comparison, Paul’s stated reason for marriage seems crass and primal. If controlling sexual desire is the only reason someone marries, then that desire may invite unhealthy or abusive sexual practices. If one partner sees the other primarily as a tool for satisfying lust, he or she is treating the other more as an object than as one truly beloved. Yet although marriage must be much more than this, the primal creaturely realities of marriage do not lose their relevance or foundational function.

Social conservatives are right to say that marriage and family are building blocks of society. Family is the place where children are cared for, learn care for others, and thus learn discipline and civility. But first good parents and would-be parents aid and care for one another as spouses.

If family is foundational for society, then marriage is the foundation for family. It is the place where spouses cement the habits, disciplines, and virtues of mutual care that we hope they began learning in their families of origin. Amid the daily ordinary, they forge a life together “for better or for worse, for richer or for poorer, in sickness and in health, ’til death do us part.”

Even when sexual desire is an overwhelming motivation and temporarily disproportionate reason for a couple to wed, marriage channels that energy and desire for closeness into the sealing of a thousand other bonds of mutual regard and mutual support. This is the unitive dimension of marriage. Then, building on this foundation, a marriage becomes generative or fruitful. As spouses support one another they contribute to a still larger community, prototypically through procreation and child rearing but also in their respective and shared vocations on behalf of the common good beyond themselves.

It is in this sense that the Pauline remark turns out not to be just about quenching lust after all. “To burn” may stand for all the ways that we human beings, left to ourselves, live only for ourselves, our own pleasures, and our own survival. By contrast, “to marry” may signal the way that all of us (even those who do so in a vocation of lifelong celibacy) learn to bend our desires away from ourselves, become vulnerable to the desires of others, and bend toward the service of others.

This is a good thing for all.

Far from being only an embarrassing textual artifact, Paul’s remark encodes the entire civilizational story of marriage. Anthropologists and paleontologists have various theories of how marriage began—whether roving men needed the resources of women more or whether childbearing women needed the protection of men more, how sexual exchange sealed and contributed to other exchanges of scarce resources or kinship, and so on. Whatever the case, one can hardly imagine civilization beginning to form at all without the fusion and coordination of cultures of women and men. Even today major social problems result when entire populations, especially of men, live lives that are unattached, except perhaps through the male camaraderie of gangs and soldiering.

This may be the truth behind the claim that men require the domesticating influence of women. To be sure, that claim has too often served to keep women in domestic roles, limit them to certain kinds of jobs, or cut them off from education and self-development. And even where the claim seems to have evidence behind it, cultural patterns have varied so much through history and across cultures that it is hard to know what the precise take-home lesson should be for any given household, much less any given society.

It’s better to focus on the work that all spouses must do to grow in habits of mutual regard, mutual support, and a shared vocation of service to others. It is this work that in turn works on them. It is this ordinary work of ordinary life that makes it “better to marry than to burn,” whatever one’s culture, household division of labor, gender, or sexual orientation.

New York Times columnist David Brooks put this well in his 2003 column “The Power of Marriage.” “If women really domesticated men, heterosexual marriage wouldn’t be in crisis,” said Brooks. “In truth, it’s moral commitment, renewed every day through faithfulness, that ‘domesticates’ all people.”

The real crisis of marriage in modern societies, argued Brooks, is a “culture of contingency.” Having learned through millions of consumer decisions to hold up individual choice as the highest value, modern humans take consumeristic habits of mind into even the most intimate of human relationships. Youthful sexual experimentation and adult promiscuity are hardly new, but modern mores and media have transformed perennial temptations into cultural expectations. Even people who hope to marry for life will “shop around” first, trying on sexual partners before committing. And though they may approximate the institution of marriage through cohabitation, even stable relationships may retain the dimension of a “trial marriage.”

Within this culture of contingency, as Brooks notes, many enter into marriage as “an easily canceled contract . . . Men and women are quicker to opt out of marriages, even marriages that are not fatally flawed, when their ‘needs’ don’t seem to be met at that moment.”

Obviously a legal or even a sacramental wedding is not a guarantee of sustained and sustaining marital bonds. Heterosexual divorce rates make that all too clear. The culture of contingency can seep into and corrode marital bonds even in what seem to be the strongest of marriages.

“But,” said Brooks, “marriage makes us better than we deserve to be.” So those who care deeply about the sanctity of marriage should resist the culture of contingency both by removing obstacles to marriage and by insisting on the link between healthy loving sexual practice and marriage.

Brooks proposed that the conservative course is not to banish gay people from marriage. “We shouldn’t just allow gay marriage,” he wrote. “We should insist on gay marriage. We should regard it as scandalous that two people could claim to love each other and not want to sanctify their love with marriage and fidelity.”

In other words, some of the best reasons to support same-sex marriage turn out to be deeply conservative ones. This suggests how the Pauline remark might provide the church with a framework for proclaiming a message of good news for all sides. It offers good news for those who are deeply concerned that we continue to hallow the institution of marriage as the only appropriate place for intimate sexual union. And it offers good news for those who are deeply concerned that people of same-sex orientation be allowed equal opportunity to flourish as human beings—that the covenanted bonds of sexual intimacy play just as much of a role in their lives.

It’s also good news that marriage need not be redefined for gays and lesbians. Marriage can and should remain a covenant and a forming of the one flesh of kinship, rather than a mere contract forming a mere partnership. Unfortunately, when advocates of same-sex marriage dismiss critics who insist that society needs a clear definition, they often default to a definition of marriage that is more impoverished than they intend it to be. As Brooks observed, they sometimes make gay marriage “sound like a really good employee benefits plan.”

Marriage will indeed be subject to endless reinvention unless we recognize it as more than a contract. Instead we should recognize and insist that marriage is the communally sealed bond of lifelong intimate mutual care between two people that creates humanity’s most basic unit of kinship, thus allowing human beings to build sustained networks of society.

Procreation will always be the prototypical sign of a widening kinship network. But as spouses in any healthy marriage know, including infertile ones, kinship is already being formed in tender, other-directed sexual pleasuring. Such pleasure bonds a couple by promising and rewarding all the other ways of being together in mutual care and service through days, years, and decades. The tragedy of abusive sex is that it uses this capacity only to take pleasure. And the tragedy of noncovenanted sex is that it forms this deep bond only to tear it apart. Even committed cohabitation leaves an asterisk of contingency on bonds of kinship, either by attempting commitment individualistically and without communal accountability, or by openly treating the relationship as a trial.

All of this, both the tragic and the good, can be said of both heterosexual and same-sex sexuality and marriage. And saying it in a single account with a single standard is one of the best things the church can do to strengthen all marriages.

Yes, Paul’s remark requires both advocates and opponents of same-sex marriage to do some uncomfortable rethinking. Thankfully, Paul has given us a biblical warrant for letting experience stretch us, for recognizing that exceptions may sometimes be legitimate, and for returning our focus to what is the good and the better.

Obviously this will stretch those who have been certain that the Bible and natural law unambiguously rule out sex and marriage except between a man and a woman. They will have to take seriously the argument that the Bible never considered the prospect of monogamous covenanted same-sex relationships. They will have to accept a biblical hermeneutic that gives greater weight to God’s invitation to people whom even the apostles considered unclean and less weight to contested texts that seem to legitimate purity codes. They’ll have to open themselves to the possibility that modern science, fresh historical study, and cultural studies require a more complex understanding of what our nature has been all along.

Yet they can welcome this stretching and this framework because it answers their deepest and most legitimate concerns. Our culture often seems to take promiscuity for granted. Although social conservatives may not be the only ones who worry about the hook-up culture of recreational sex, the wider culture expects people to practice a kind of slow-motion promiscuity. Adultery is still considered wrong for married couples, and couples that are dating or “together” should have sex only with each other, but partners are expected to check out sexual compatibility as part of a tentative, exploratory commitment. A succession of sexual partners is thus seen as normal, as long as each relationship is at least vaguely “committed.”

This culture of contingency troubles many of us, and some react negatively to homosexuality or same-sex sexual activity because it seems to them the final breakdown of boundaries and propriety. Gays and lesbians rightly object to the implication that they are especially promiscuous. But at least within debates over same-sex marriage, they lose nothing by stipulating the concern, if only for argument’s sake. After all, any confirmation of a greater tendency toward promiscuity among certain demographics, probably male, would provide more support for same-sex marriage!

An area of consensus begins to emerge: a chief reason for our uncertainty about gay promiscuity is that for a long time gays and lesbians had no culturally recognized or legally protected paths by which to develop healthy sexual relationships. Within the church they could not even embrace a celibate vocation with a fully human yes because no other healthy and recognized option was available to them. If they’ve been left to “burn,” as Paul said, it’s because they could not marry.

Extending the blessing of marriage to same-sex couples will in fact counter the culture of contingency and promiscuity among heterosexuals as well as gays and lesbians. The blessing to all may encourage marriage among heterosexuals—my wife and I have both heard straight young people say that they hesitate or even refuse to marry until marriage is available to their gay and lesbian friends. And while a complex array of social and economic factors contributes to increased rates of cohabitation, withholding the blessing of marriage to gays and lesbians hardly helps. If cohabitation is the only way for them to live in monogamous covenanted relationships, then it becomes a more prominent, increasingly normalized model of relative faithfulness. If Christians are going to continue to insist that public accountability within communal support systems is an essential condition for greater and more permanent faithfulness, then weddings should be open to all.

Meanwhile, those who’ve advocated for same-sex marriage chiefly in the language of rights and freedoms will also be stretched. They will have to acknowledge that their opponents have rightly pressed for a clear definition of marriage and provide much better answers. After all, one cannot really recognize a right to something without knowing what it is.

Furthermore, it stretches many in our culture to recognize that the fullness of human freedom is to be found in capacity and not simply in autonomy. In other words, freedom requires more than mere license or freedom from restriction. It also requires the skills, habits, and virtues to live well and richly—freedom for. In turn, the freedom of capacity requires a formation that includes discipline. (Think here of all that’s required to develop the freedom to play virtuoso piano or excel as an athlete.) Advocates of same-sex marriage should reaffirm that the discipline of chastity, in preparation for the discipline of marital fidelity, is actually freeing.

Yet they too can welcome this stretching and this framework because it answers their deepest and most legitimate concerns—it opens up equal access to marriage and acknowledges the need to correct for limited understandings of the nature of same-sex orientation. It acknowledges the painful injustices. Then it welcomes the opportunity for all to thrive, not as gay or straight, “queer” or “normal,” but as human beings who need to find life-giving forms of personal intimacy.

The stretching that’s required is also an opportunity. Gays and lesbians might say something like this: “Part of the injustice of the past is that we have not had good options for chaste courtship, socially and ecclesially supported marriage, or authentically chosen celibacy. Together these would have given us the opportunities that straight people have had to explore their sexual identities without extra pressure for sexual experimentation outside of marriage. Escaping this tragic injustice allows us to reaffirm that God intends active sexuality to take place uniquely within marriage. Discarding excuses for refusing to bless same-sex relationships goes hand-in-hand with discarding excuses for sex outside of marriage, straight or gay.”

In this view, marriage is not simply an oppressive institution to be dismissed as heterosexist. As a heterosexual I recognize that I cannot help but write this from outside the direct experience of gays and lesbians. But surely this is implicit in the entire social and legal movement for recognition of same-sex marriage. All sides will be helped if all sides can affirm this.

If this proposed framework for a churchwide consensus feels like a grand compromise, that in itself is not a bad thing. Uncomfortable concessions can be a sign of having listened deeply to one another. And anything that allows Christians to engage society together through a positive and reconciled witness rather than defensive postures will be welcome.

But I believe this is much more than a compromise. It brings us together in the biblical witness and wisdom of Paul himself. It allows the church to make its teaching on the nature and sanctity of marriage clearer. And it allows us to turn our energies to working on the real challenges to marriage in our age.

It would be foolish to claim that this framework alone will resolve everything. Easy access to pornography, the hook-up culture, and media portrayals of recreational sex as the norm are difficult to counter. The social expectations that are producing ever more exorbitant wedding events do not get the attention they deserve.

The widening practice of cohabitation is vexing in another way. Young people hesitating to vow themselves to one another permanently are perpetuating the culture of contingency even though they have often been its victims—for example, as children of divorce. And even if the contingency of cohabitation makes lasting relationships somewhat less likely, it does approximate and thus honor marriage in some ways.

So the church and its leaders need great pastoral wisdom to do two things simultaneously:

- Walk back from the culture of contingency by explaining and insisting in fresh ways that God intends for active sexuality to belong uniquely to marriage.

- Work compassionately with those who have embraced the relative fidelity of cohabitation, even if they have not yet moved to embrace a covenant of marriage or a vocation of celibacy.

If we aim for these two goals, Christians will be better able to speak clearly and work energetically because together we’ll affirm that marriage is good—for everyone.