The prodigal's brother

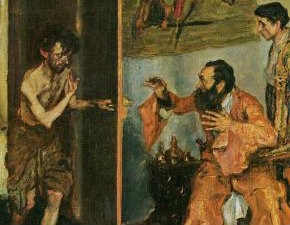

When I preach on the parable of the prodigal son, I always get stuck on the elder brother. I wish there were a fifth gospel in the New Testament devoted to reaching out to that guy because he's everywhere in the congregation I serve, wearing many names and faces. Frankly, we depend on elder brothers to keep the place running. But I struggle to know how care for them.

I've tried giving elder brothers more stuff to do because they happily accept, and I've tried encouraging them to work to create a more just society because I know they think it's up to them to get things right. But both of these strategies miss the point of this parable—and the gospel of grace.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Most preachers know how to proclaim grace to the prodigals. "It's OK," we keep saying, "God knows what you have done, but you are forgiven. All you need to do is come home and accept the forgiveness that is waiting for you." We can make those words sing for those who have screwed up their lives, but what does the gospel say to the elder brother who spends his life playing by the rules?

It is tempting to make him into a bigger sinner than he is. This is not without biblical warrant since Jesus kept saying things like, "All your righteousness is as filthy rags." But it's a mistake to conflate the elder brother with the prodigal. They have different roles in the story, and the role of the elder brother is to demonstrate the dilemma of those who don't know how to get into the arms of the father that are outstretched to prodigals.

The sins of the elder brothers are, well, boring. When one of them comes to see me claiming to want to make a confession, I usually hear, "I have agreed to coach my daughter's soccer team because no one else would, and we will be moving my aging mother-in-law into our back room, and the church's tutoring program for inner city children is expanding way beyond our expectations—so would it be OK if I didn't chair the stewardship committee next year?"

I want to say, "That's it? That's your idea of a confession? I can do better than that. Let's change seats." So it doesn't really work to try to convince elder brothers to act like prodigals. They're just terrible at it.

Scripture makes it clear that repentance is a necessary response to the salvation of Jesus Christ. But of what do the righteous repent? Sin is anything that keeps us from God. So as odd as it sounds, the elder brother has to repent of the righteousness that is keeping him from needing Jesus. But it is much harder to repent of being good. The elder brother has been rewarded his whole life for getting an A on every test, and he knocks himself out to earn this stellar transcript. But when he comes to church he hears that in the end it's a pass/fail test, and the only way to pass is to receive the grace of God. "It's not about what you achieve, but what you receive." When I say these things in a sermon, the elder brothers cock their heads like faithful dogs do when they're confused.

I remind them, as the father does in the parable, that they already have all they ever wanted out of life. They readily agree that everything truly important to them has come by grace and not through their hard work. But I have to remember not to leverage their gratitude by saying, "Get back in the fields of hard work." The invitation of the father is for his elder son to come to the celebration.

Over the years I've learned that the elder brother has another besetting sin, which is anxiety. Prodigals don't stay awake all night fretting that they haven't done enough. That's the burden of those who carefully try to construct life. When can anyone do enough? Anxiety always tags along behind the drive to do well. The Bible has plenty to say about the perfect love of God that alone casts out fear. We can never be rationally convinced to give up anxiety. It's an emotion, and only the emotion of God can get rid of it. So I preach often about the Savior who was literally dying to love us.

In the parable, the elder brother seems anxious about the fuss made over the return of his brother. The subtext of that worry is that he doesn't feel appreciated. Yet his carefulness and propriety make him uncomfortable with his father's passion.

This teaches me that I can't just say a polite thank-you to the workers who keep our church rolling along—I have to give my heart to them. My job as a pastor is to incarnate God's passion for everyone, including those elder brothers who back up a bit when I say, "You are so cherished."