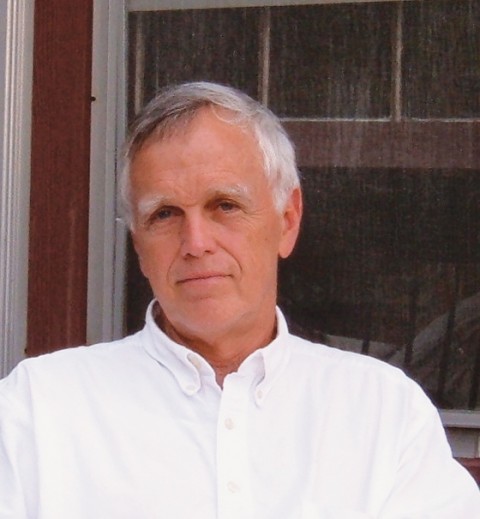

Religion and the ridiculous: Novelist Clyde Edgerton

A critic once called Clyde Edgerton the "love child of Dave Barry and Flannery O'Connor"—a reflection of the fact that his novels are both dark and funny. His nine novels include Raney, Walking Across Egypt, The Floatplane Notebooks, Killer Diller and, most recently, The Bible Salesman, about a young man who has never read the Bible but is selling it door to door. Edgerton teaches at the University of North Carolina at Wilmington.

In a recent interview, you spoke about being compelled to go back to church after many years away from it. What compelled you? Did your return disappoint or surprise you?

I love the old hymns, and my wife and I wanted a place for our children to systematically receive moral teachings to underpin daily life. Not that we didn't need the same.

My return to church has not disappointed me because we found a Baptist church [Winter Park Baptist in Wilmington, North Carolina] whose minister [Eric Porterfield] stresses love of neighbor and racial reconciliation. He doesn't stress eternal damnation or eternal bliss.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Are there aspects of your religious heritage [Southern Baptist and fundamentalist] that you admire and hold on to?

I've come to appreciate Bible narrative. What great stories of wrestling, beheading, brain-dashing, compassion, loyalty, service, lost love.

I think that I almost unconsciously hold on to the fact that as a child in my church I felt protected, felt the warmth of people older than me. They were like aunts and uncles in many ways, even though I was afraid of the anger and loudness in many of the sermons. I felt protected from the anger of God by the warmth of the adults. How could they have lived long lives with the same God that some of my preachers said was out to get me? I allowed a tip of the balance toward the warmth of old people and never felt too uncomfortable in church until I got old enough to think for myself.

In your books there is often a remarkable interplay between the religious and the ridiculous.

There seems to be such an interplay between the ridiculous and most facets of our lives: family life, politics, social norms, education. Religion doesn't get off the hook in real life so it shouldn't in fiction. Because religion was one of the most serious aspects of my early life and because I believe that humor is one of the human stays against chaos, I end up mixing humor and religion.

What is happening now in southern fiction?

Fiction writers are still dealing with that species of animal called human in a hot place where there's plenty of reactionary fundamentalism and family loyalty and a history of living close to the land, along with a poverty that often finds little hope in the promise of America.

You once said, "Because I was born in the South, I'm a southerner. If I had been born in the North, the West or the Central Plains, I would be just a human being." Do we make too much of southern culture generally or of southern literature in particular?

Maybe we do make too much of it—because it's often loud and in the case of good fiction, accurate. Whereas various media interpretations of the South are sometimes only loud. It's always a bit of a downer for me when those not from the South start talking about front porches and sweet iced tea and quirky characters. I visualize the caricatured life and predict the next string of dead mule generalizations.

Does your work as a musician inform your writing and vice versa?

It's fun to think about how writers improvise like musicians improvise. How do we use redundancy to our benefit—how far may we wisely drift from the melody?

I'm also finding predictable and interesting parallels between writing and oil painting. The framing in either (while deciding the theme) may kill or bring alive the content. And the use of detail in the painting is, of course, not unlike choice of detail in a literary scene. The right detail can bring life to a scene, and the wrong one in a story may distract a reader and mute the writer's intention.

Do you follow contemporary debates on the Bible and theology? Do you ever get any story ideas from them?

I've written three books that depend indirectly on Bible stories for novel content. It's fascinating to pretend to be a person reading the Bible for the first time, as I have in a couple of novels.

In doing research about various Bible translations before writing The Bible Salesman, I came upon Harold Bloom's Yahweh and Jesus: The Names Divine. I found ideas in Bloom's book that led to conversations among several house cats in my novel. Worried (from a literary perspective), my editor asked, "What in the world are you doing?" I reluctantly realized I was using too many of those conversations, but she and I agreed that I could keep a few. Those conversations came to the forefront in a musical radio play that my musician friend, Mike Craver, and I put together a couple of years ago. [The radio play, The Bible Salesman, by Edgerton and Craver, is available on CD from sapsuckermusic.com.]

How would you describe the ways that grace appears in your fiction?

I've never thought about it, though I have thought about that topic as it relates to Flannery O'Connor's fiction, and I've not been able to come up with a clear answer. I would say generally that grace shows up in my fiction through the actions and intentions of individual characters. I have a hard time understanding definitions of grace that assume a very large man, dressed in white, handing out grace-candy from heaven.

Are religious people ever offended by the humor in your books? How do you respond to them?

Yes, some religious individuals have been offended by my attempts at humor. (I just realized I may have in fact lost a reader or two on the grace thing above.) I've received a few letters and comments and have read reports about and by people who are offended. I try to publicly accept their perspectives with grace, while internally I curse—not them, but their sin.